1. Lesson 15:

Special Relativity, 1¶

Confusion about light.

What’s Coming:

Arguably one of the most important experiments in the last two centuries, and certainly the most important measurement ever of zero, starts in the Wild West of gold and silver mining – literally, the Wild West – and passes through Stockholm and the Nobel Prize. Let’s talk about one of the more interesting physicists of all. Albert Michelson.

1.1. A Little Bit About Michelson¶

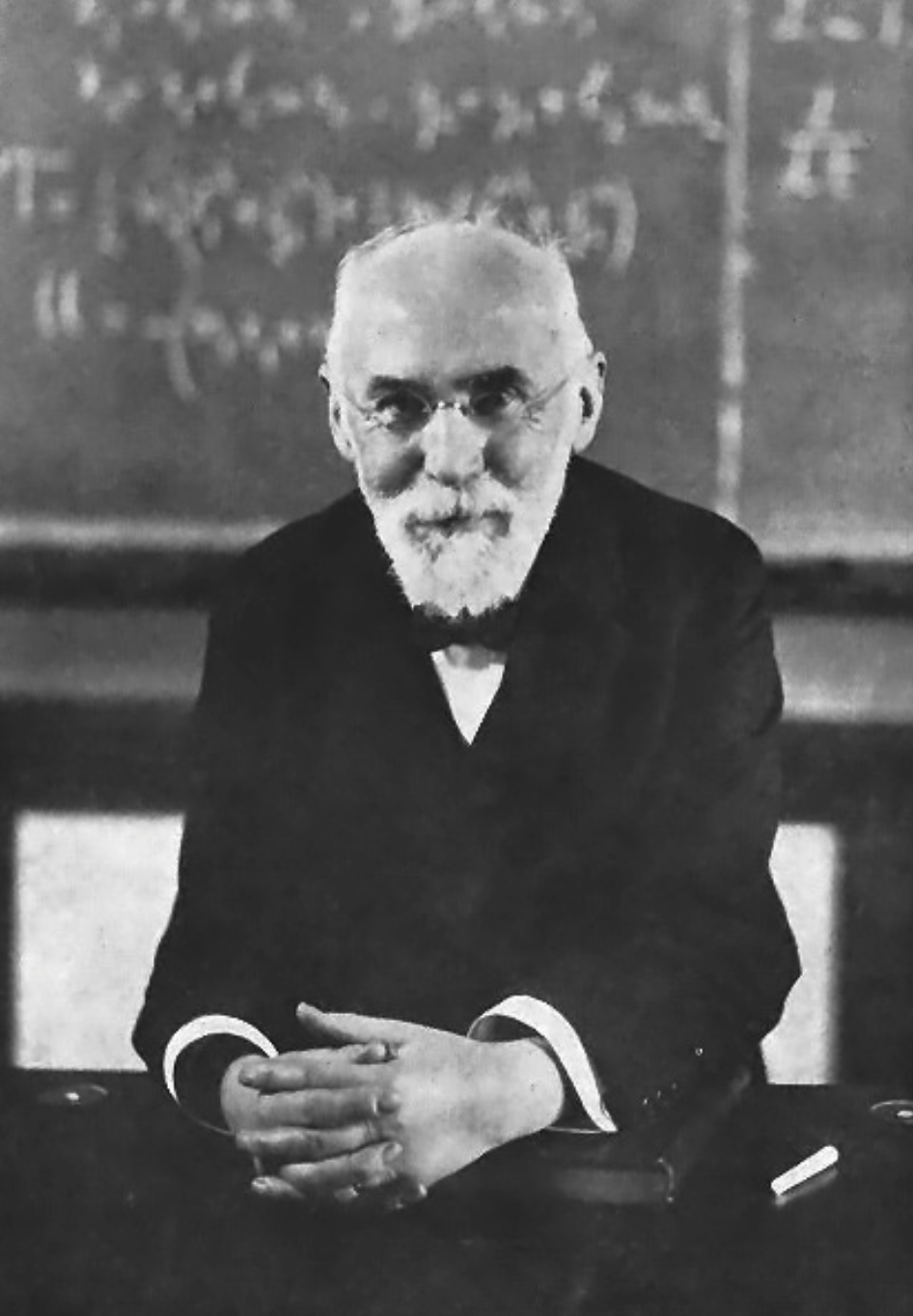

Fig. 1.1 Albert Michelson

1852-1931¶

Faced with a difficult situation, he did what any mid-19th century 16 year old would do: he boarded the brand new Transcontinental Railroad at Oakland Land Wharf in San Fransisco and went to Washington, D.C. to see the president. Albert was nothing, if not persistent.

Albert Michelson (1852 - 1931) was born in Poland and as a two year-old with his merchant-class family moved to the United States. The Michelsons were adventurous — facing hardship in Poland, they resolutely traveled to the wild west (a harrowing passage through lawless and diseased Panama) and became store-owners in various mining communities in California and Nevada, settling in the nearly untamed Murphy’s Camp, California. A bad cowboy movie, lawless, gold-rush western town. His mother exported Albert to relatives in San Francisco where excelled in high school. College was in his future but his path was unusual: he applied in a competition to the relatively new United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland and was rejected. Hence, his audacious trip to see President Grant who received him at the White House and eventually personally admitted him (above the prescribed number of cadets) to Annapolis as a midshipman in 1869. He graduated and did his two years at sea and returned to the Academy as an instructor. He always joked that he was probably illegally a student at the Naval Academy.

He fell into measuring the speed of light as a laboratory exercise for his students. This had only been measured on Earth 15 years earlier when Léon Foucault at the Paris Observatory created a clever apparatus involving a precisely measured rotating mirror to do so. Foucault found \(c= 313,000,000\) m/s with a precision limited by the length of the light path in his instrument. It was Foucault’s result that clued Maxwell into the fact that he’d found a model of light that worked.

This was the technique that Michelson adapted for his midshipmen students and by 1879, he’d improved on the results by a factor of 20 finding \(c=299,910,000 \pm 50,000\) m/s. (He never quit. In 1924 he improved this to \(c=299,796,000 \pm 4,000\) m/s with a light path stretching across the hills outside of the Hale Observatory near Pasadena.)

The rest of Michelson’s life was consumed by making precision instruments to measure various features of light. He was the King of Optics – the master experimentalist in the measurement of precision optical phenomena leading to heroically precise techniques to measure \(c\) to very high precision. His expertise allowed for a leave of absence from the Navy and the opportunity to study in Germany for a while and to return to making increasingly better measurements of \(c\). He was working on such a measurement using a mile-long evacuated tube when he died in 1931.

Fig. 1.2 Murphy’s Camp in 1852 a few years before the Michelsons arrived. Literally tens of millions of dollars in gold was shipped out of Murphy’s Camp in a few years and so it was bustling, but full of drunks, violence, public hangings, and hard edges. Things were going well until the entire town burned to the ground in 1859 in less than an hour.¶

Michelson was notoriously stern and difficult (although he was an accomplished artist, musician, tennis player, and billiards player). He also led an interesting life. His first wife tried to have him committed and a maid sued him for abusive solicitation. He once had an argument about an experiment with a colleague in a hotel lobby that drew a crowd, maybe because they were loud and maybe because Michelson was still in his pajamas. He won the Nobel Prize in 1907, not for his most famous measurement of zero, but for his exquisitely precise instruments and the collection of scientific measurements that he made with them.

1.2. That Zero: “…it is absurd to imagine”¶

As a graduate student in 1880 in Hermann von Helmholtz’s famous Berlin laboratory, against everyone’s advice, Michelson decided to follow an off-hand comment of Maxwell’s in a letter written the year before, during his last year of life. Maxwell imagined a way to measure the speed of the Earth relative to the fixed ether, but lamented that the precision required was beyond any terrestrial technique. This captured Michelson’s attention and the speed of light went on the back-burner as he embarked on his most important – and personally disappointing – experiment.

1.2.1. What’s Waving?¶

What’s more ridiculous than a wave that has nothing to wave in?

Fig. 1.3 Water is the medium in which water waves propagate. What could be more simple?¶

From the time of Aristotle, it was assumed that empty space was not empty, but consisted of a strange substance archaically called “aether” and in the 19th century, “ether.” The persistent belief in this substance was reinforced in the 19th century when Newton’s demand that light consisted of particles was dethroned by (the young) Thomas Young’s (unwelcome – he was drummed out of British science for disputing Newton) demonstration that light consisted of waves. This was the passage of light through two slits, showing that the emerging waves diffracted – only waves do that. We considered that in detail in a previous lesson.

Maxwell’s subsequent unification of electricity, magnetism, and optics into a single model of waves of electric and magnetic field vectors and Hertz’s demonstration of their existence made it clear: light, electricity, and magnetism are waves and so it has to propagate in a substance which supports that disturbance. The ether was to light as water is to a dropped pebble and air is to sound. And nobody imagined otherwise. Sir Oliver Lodge was passionate (and relentless) on the subject, even after it was clear he was wrong:

… it is absurd to imagine one piece of matter acting mechanically on another at a distance, whether that distance be large or small, without some intervening mechanism or connecting link…

1.2.2. But Maxwell Said c!¶

There was a serious fundamental problem. The solution to Maxwell’s equations is indisputably a wave and furthermore, the speed of that wave is a single number, \(c=300,000\) km/s. But with respect to what? Maxwell’s model didn’t include the freedom for it to be \(c\) plus whatever the speed of an emitter might be…like walking with a lantern. No. The speed of light is a fixed value and everyone, including, and especially, Maxwell believed that the ether provided a fixed reference and that the speed of light – and the light waves themselves – were fastened to that material.

The ether was a very strange beast. If you were to do an experiment (that you should not do) involving a railroad track and a hammer, you would find that sound travels faster in a solid than in air. If your (former) friend bangs on a railroad track a 100 yards away, and if you put your ear to the track, you’ll hear it through the metal before you hear it through the air. Now, get off the track. That’s dangerous.

In fact the speed of a wave in a medium is dependent on the square root of the “stiffness” (called the “bulk modulus”) of the material – steel is a million times stiffer than air, so the speed of sound in steel would be 1000 times faster.

Now light is the fastest thing there is! So turning that argument around, the stiffness of the ether must be incredibly higher than even steel. And yet, the ether needs to be easily plowed through by the planets that presumably swim around in their orbits through it while they delicately reflect their light back to our telescopes. How can a substance offer no resistance to a planet’s motion (or even a car, or a person, or a bird) and yet be incredibly stiffer than steel?

No matter. A detail. It’s actual existence, while required, seems circumstantial. There had to be an ether in order for their to be a wave of light. It seemed to have two functions:

As I remarked above, Maxwell created his four equations for electricity and magnetism, out of which popped the mathematical representation of a transverse wave, the speed of that wave, “\(c\)” was required by him to be the speed of light relative to the ether.

Newton insisted that space was a “thing,” a property of the universe and that there is an absolute coordinate system (Absolute Space) against which all motions – constant velocity and accelerated motions – could be measured. The ether seemed to be that perfect construct: it and only it would function as that absolutely at-rest structure that anchors space.

The question is how do we detect the ether? Michelson set out to determine our speed as we move through it.

1.3. Moving Through The Ether¶

A naval analogy, as described by Michelson to his children.

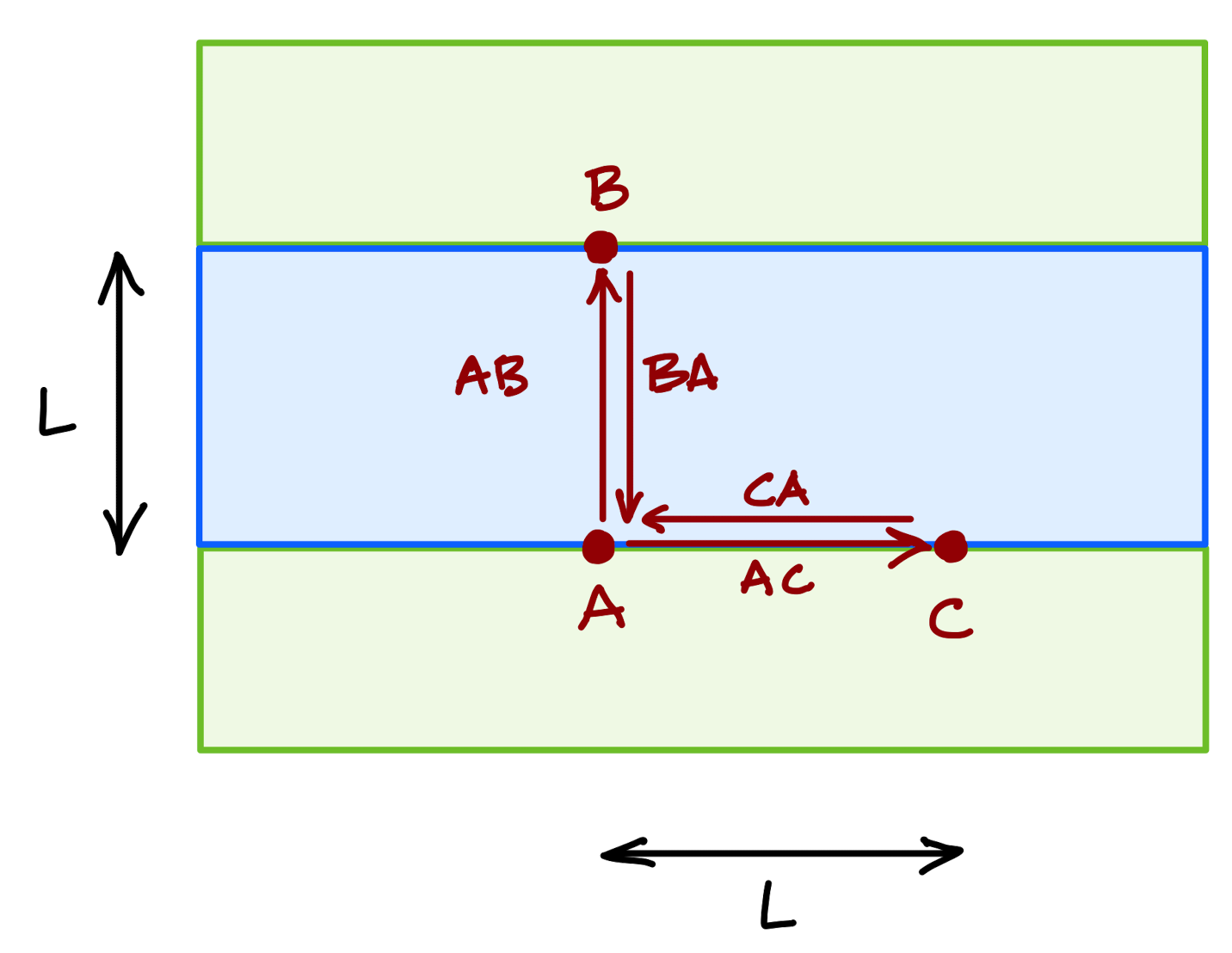

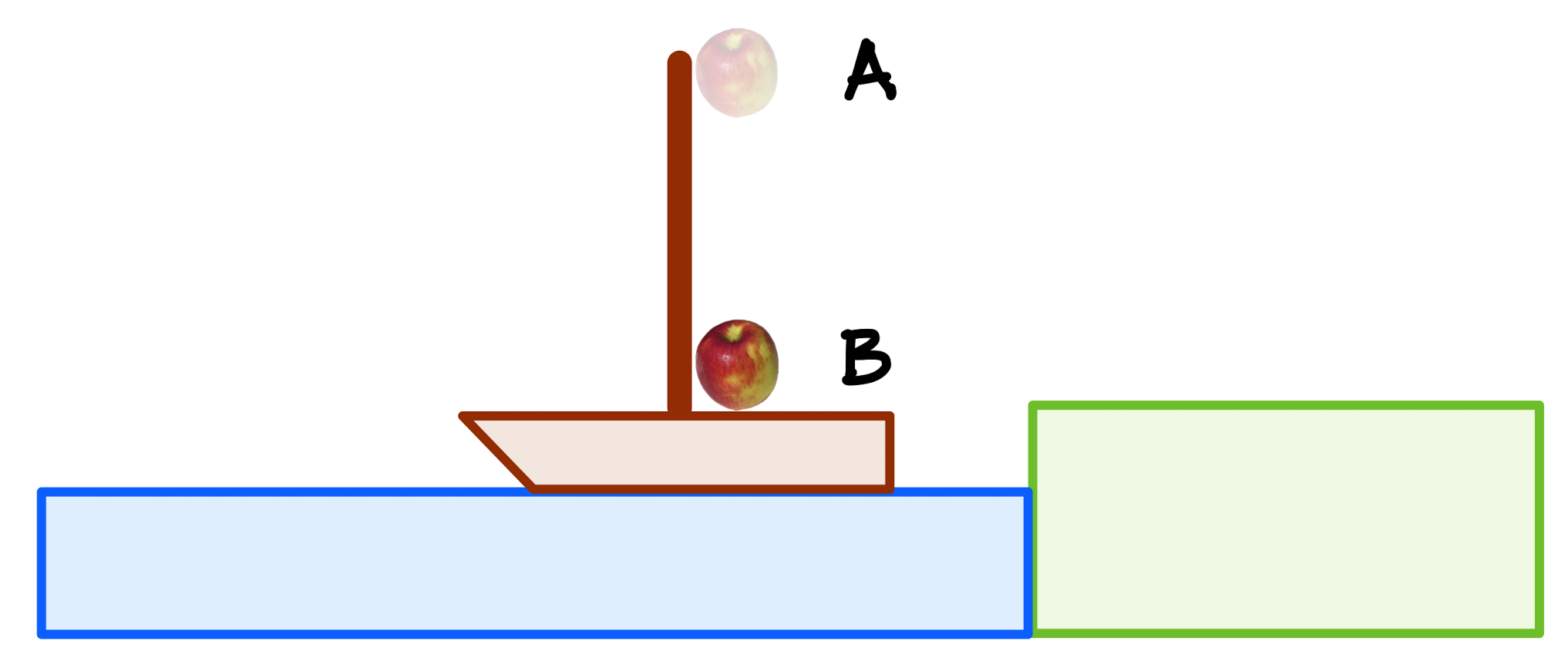

Suppose you and your friend are standing by a river and ready to race. The river is still as shown in the figure and you each plan to pilot your motor boat a distance \(L\), starting at point \(A\) and ending at point \(A\). One of you goes across the river (\(AB\) to \(BA\)), and the other of you to the right and then left (\(AC\) to \(CA\)). Who wins if both boats can move through the water at the same speed?

Pencils Out! 🖋 📓

Fig. 1.4 MARGINCAP¶

Obviously, both of you are traveling at the same speed, over the same distance and if the water is perfectly still (no current), your race from \(AB\), \(BA\) compared with \(AC\), \(CA\) would result in a tie. That’s too easy.

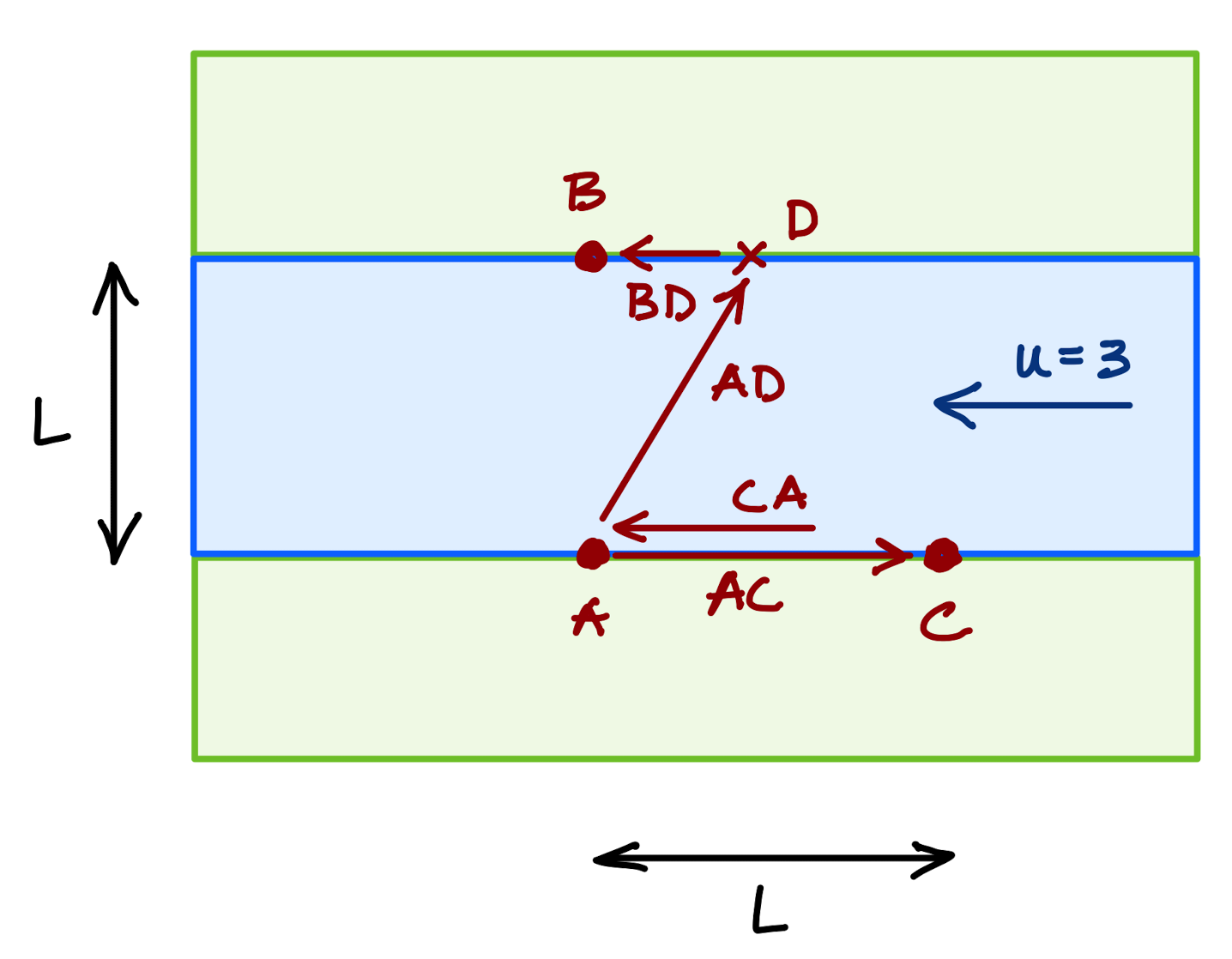

Now suppose that the river has a strong current to the left. I take the right-left trip and in the first leg, \(AC\) I must go against the current while the return \(CA\) is helped by the current. By contrast, you take the trip \(AB\) but you can’t go directly across the river since your boat would be carried downstream, so you must aim your boat to the right at just the right angle to drift to \(B\) as you plow through the water at your regular speed. Then you return has to be the same thing.

Fig. 1.5 MARGINCAP¶

Who wins?

Well, it turns out that the round trip across the river will be quicker than the trip to the right and to the left.

Now suppose we make the following substitutions in our nautical race:

boat\(\to\) light beams

river\(\to\) the ether “wind” as the Earth passes through it

bank\(\to\) the Earth

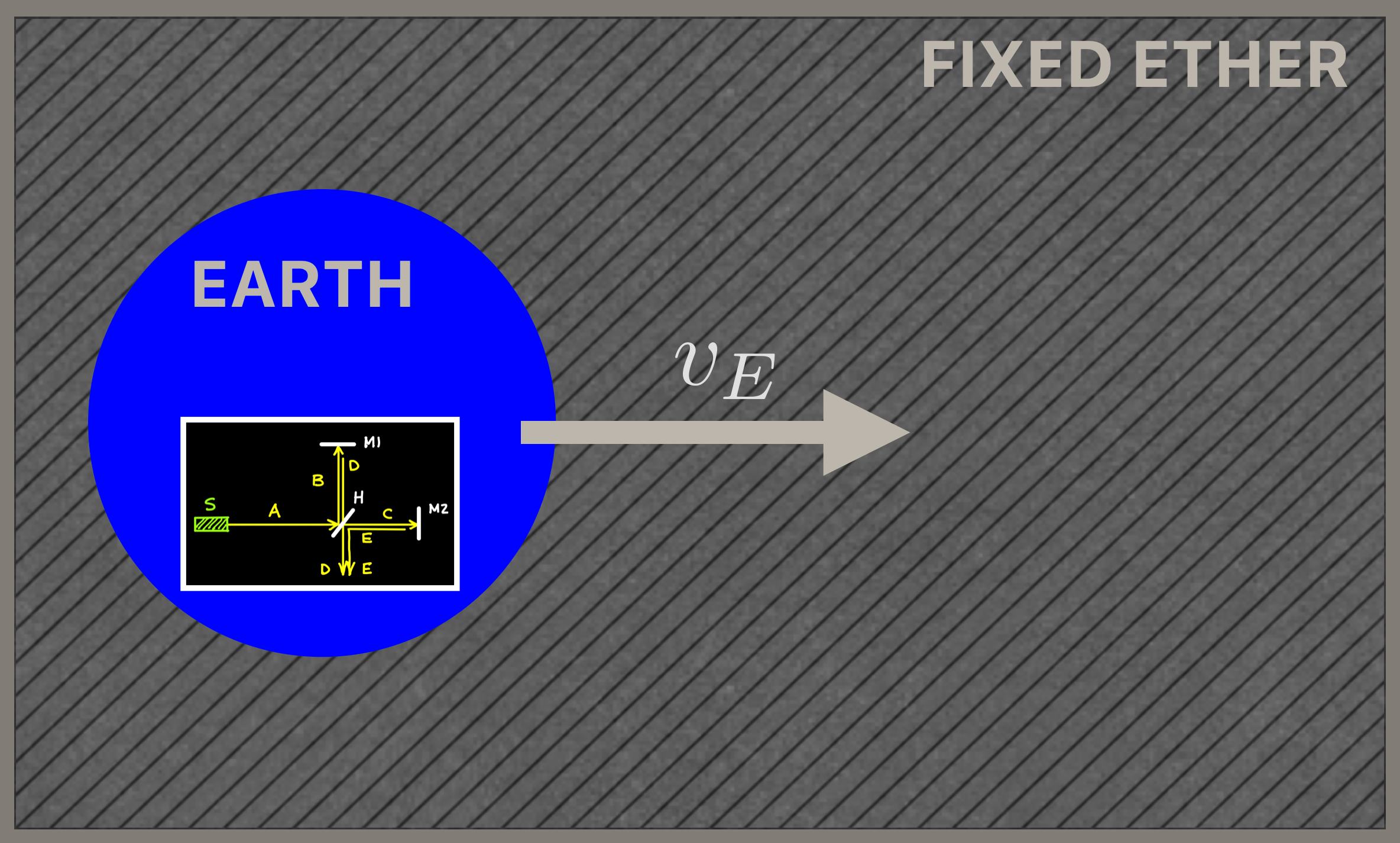

From the position of the Earth, the ether moves past to the left as the Earth moves in its orbit, here to the right. So on Earth we should detect a constant “ether wind.” Or a current to the left. Here is Michelson’s instrument riding on the Earth and together they move through the fixed ether:

Fig. 1.6 The grey background represents the ether (Newton’s fixed frame) and the blue sphere, the Earth passing through it in its orbit at a velocity, \(v_E\). On the sphere you can just make out Michelson’s instrument riding on the Earth and so also passing through the ether. Or is it?¶

1.3.1. Michelson’s Interferometer¶

How did he do this? The instrument he invented and spent his life perfecting is called the Michelson Interferometer and it’s a standard tool in today’s laboratories in optics and even astronomy.

Pencils Out! 🖋 📓

Here’s the idea:

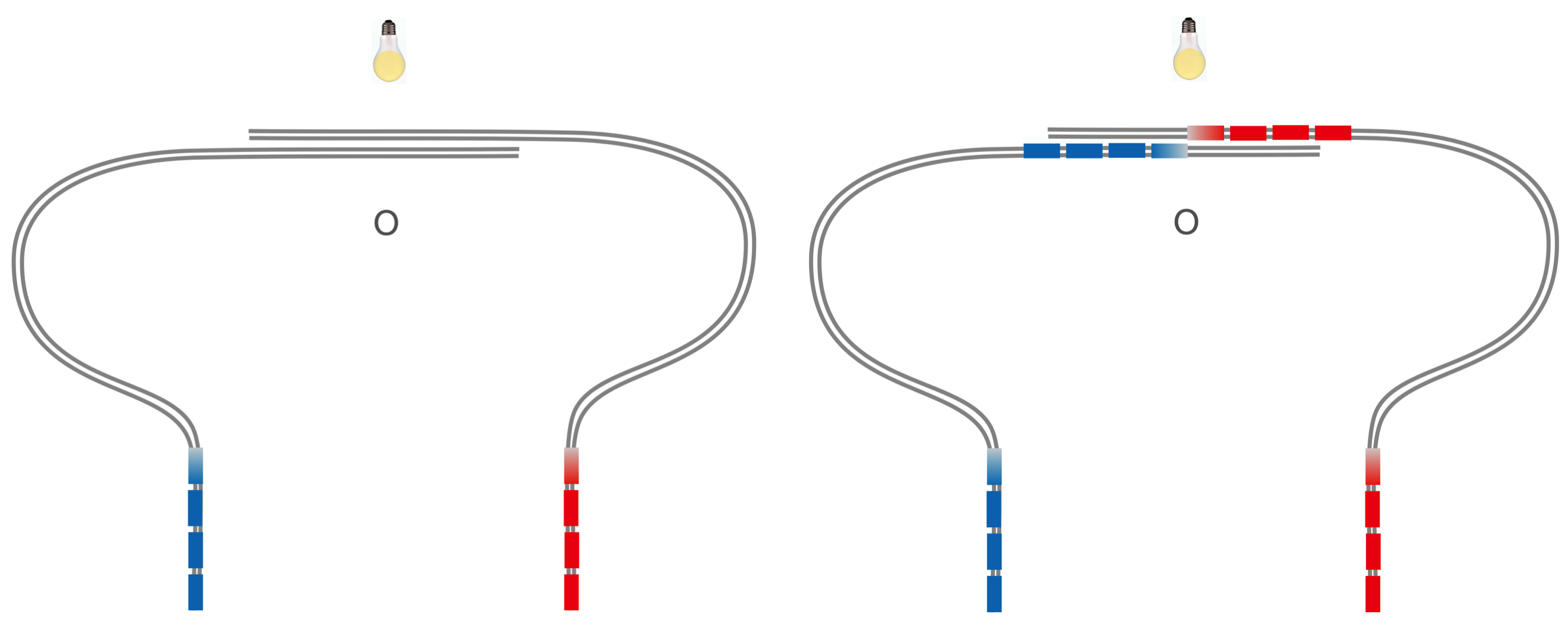

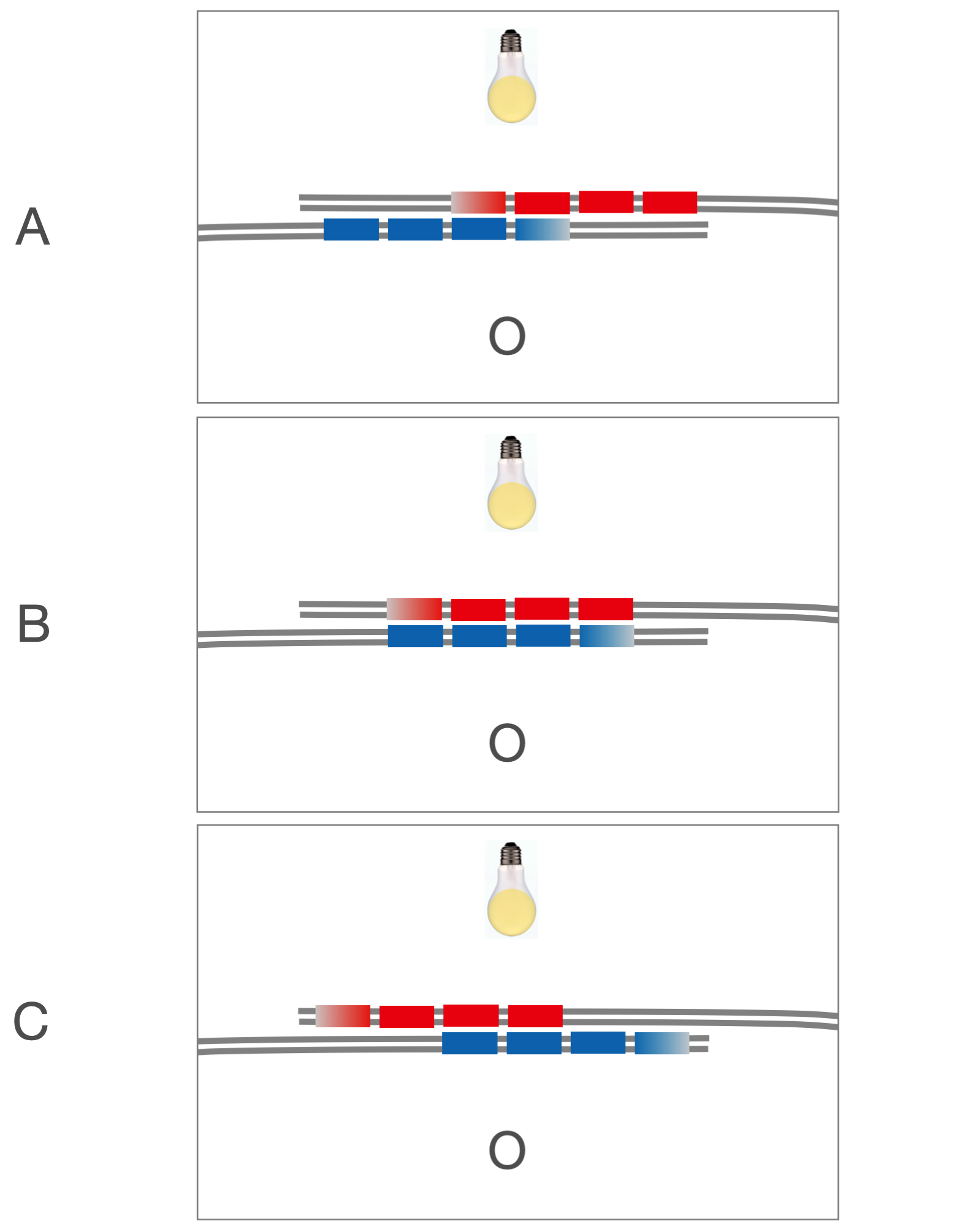

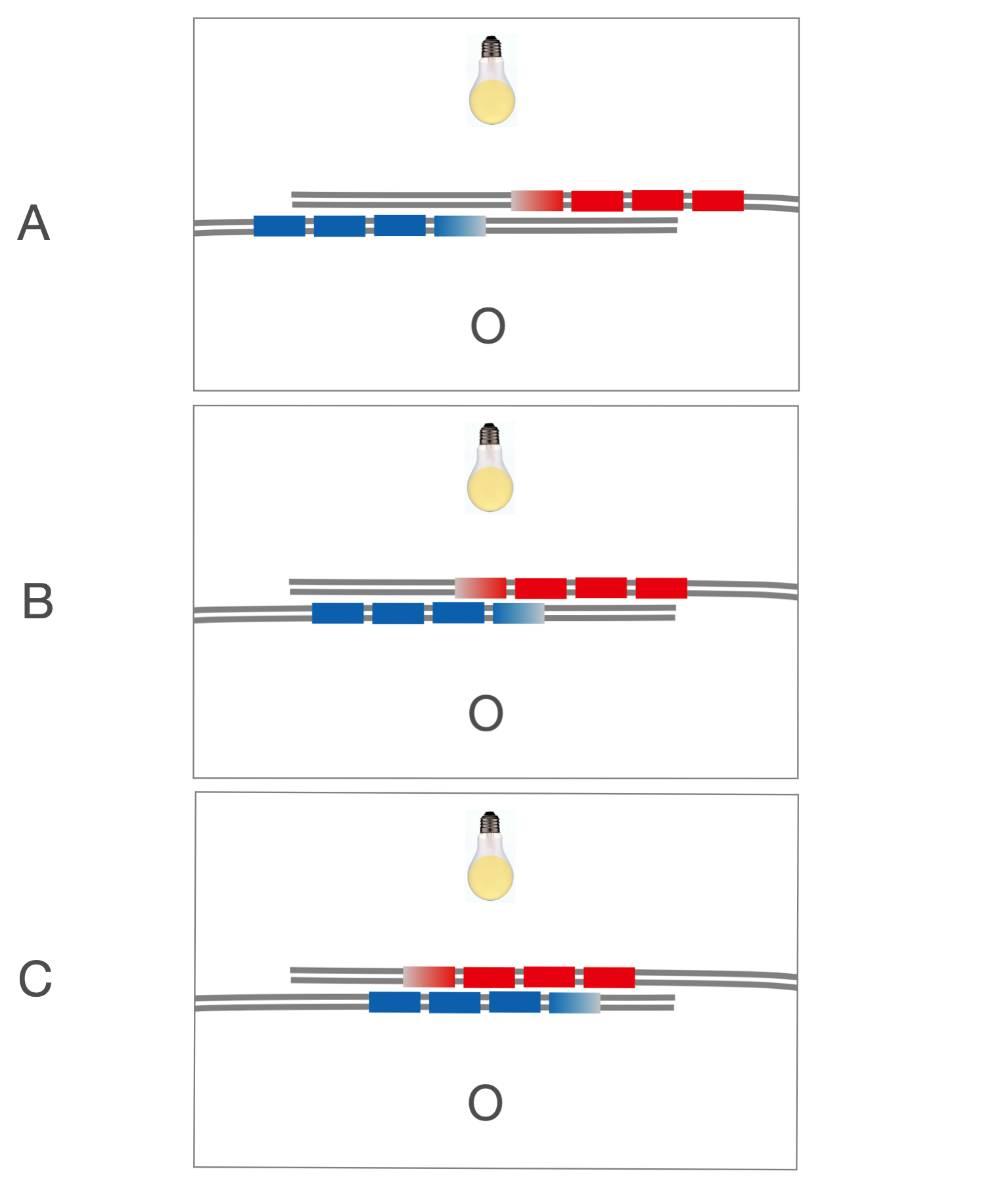

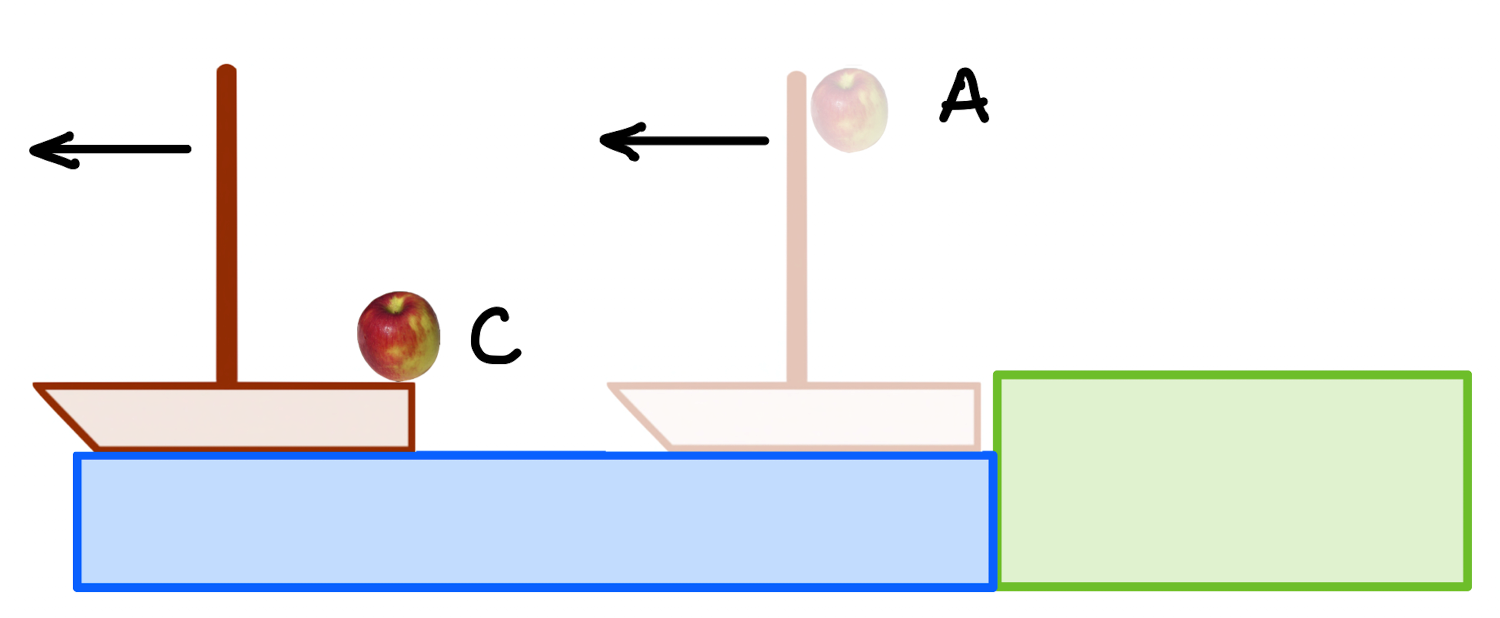

Suppose we have two identical trains that leave the station on identically constructed tracks at precisely the same speeds. Each train has 4 cars, each car is exactly the same length, and the spacing between the cars is exactly the same. Our little trip is kind of boring. It consists of the following set of loops created so that the tracks and so the trains pass one another at the top. We’re at point \(O\) and there’s a light source on the other side of the trains from us.

Fig. 1.7 Two trains are coming towards one another from the left and the right. From the left, is the blue train and from the right is the red one, and both have the same number of cars. In the left figure, they’re just starting their trip.

The right figure shows when they are just about to pass by one another in they synchronized trip. We stand at point O and we’ll watch for light from the bulb on the other side of the tracks.¶

On the left, this figure shows the trains just starting out on their trips. On the right they have reached the mid-point and are just beginning to pass one another. Notice that the fronts line up with blue going right and red going left.

Let’s look at successive times. From A to B to C, we have snapshots of the train positions from early to later times. In each case, the gaps between the cars line up and from O we can see the light.

Fig. 1.8 Now they are starting to pass by. In A, the first cars have passed, and since they are perfectly in sync, the light shines between them in the space that briefly opens up. In B, two cars have gone by and again, the openings between the cars line up and we see the light. In C, again. Just right.¶

Now, lets’ mess with them and make the right-hand track just a tiny big longer than the left-hand track. Same trains. Same speeds. Now the left-hand blue train reaches \(A\) slightly before the right-hand red train, right? So the gaps are out of phase and you don’t see the light except only occasionally. From top to bottom, we can see that the gaps never will line up.

Fig. 1.9 Now, we’ve messed with the synchronization and the two cars from red and blue are not in time with one another and the likelihood of seeing the light? Very small. It’s blocked.¶

Suppose (and I don’t know how to build this), the right -hand track is not getting longer, but moving away toward the right, away the other one by stretching the track. Can you see that this too would make the gaps not line up, except only occasionally?

That’s the principle behind the Michelson Interferometer. Instead of trains, he used light. Instead of gaps, the peaks and valley’s of the light waves either would be in phase and get bigger in synch – like seeing through the gaps between the cars – or they would not and interfere and you’d see the peaks diminished or even gone.

Michelson invented and built (on Earth!) a first version of an instrument that sent a beam of light in one direction, like \(AC\) on the river and at the same time a second beam of light in a perpendicular direction, like \(AB\) on the river. Then with mirrors he brought them together back at \(A\) to see who wins. What determines winning?

Well, light is a wave and when two waves encounter one another, they mix and interfere. Where the two waves are in-synch, the result is a new wave that’s big at the position of the original common peaks. Where they’re out of synch? Well, then you get a quiet result–no wave (think of your noise-cancelling headphones). If they’re somewhere in-between, then there’s a peak, but it’s not where the peak is for either of the two initial waves. So calibrate your instrument carefully for both beams in-synch and then turn it loose on the ether and see what happens.

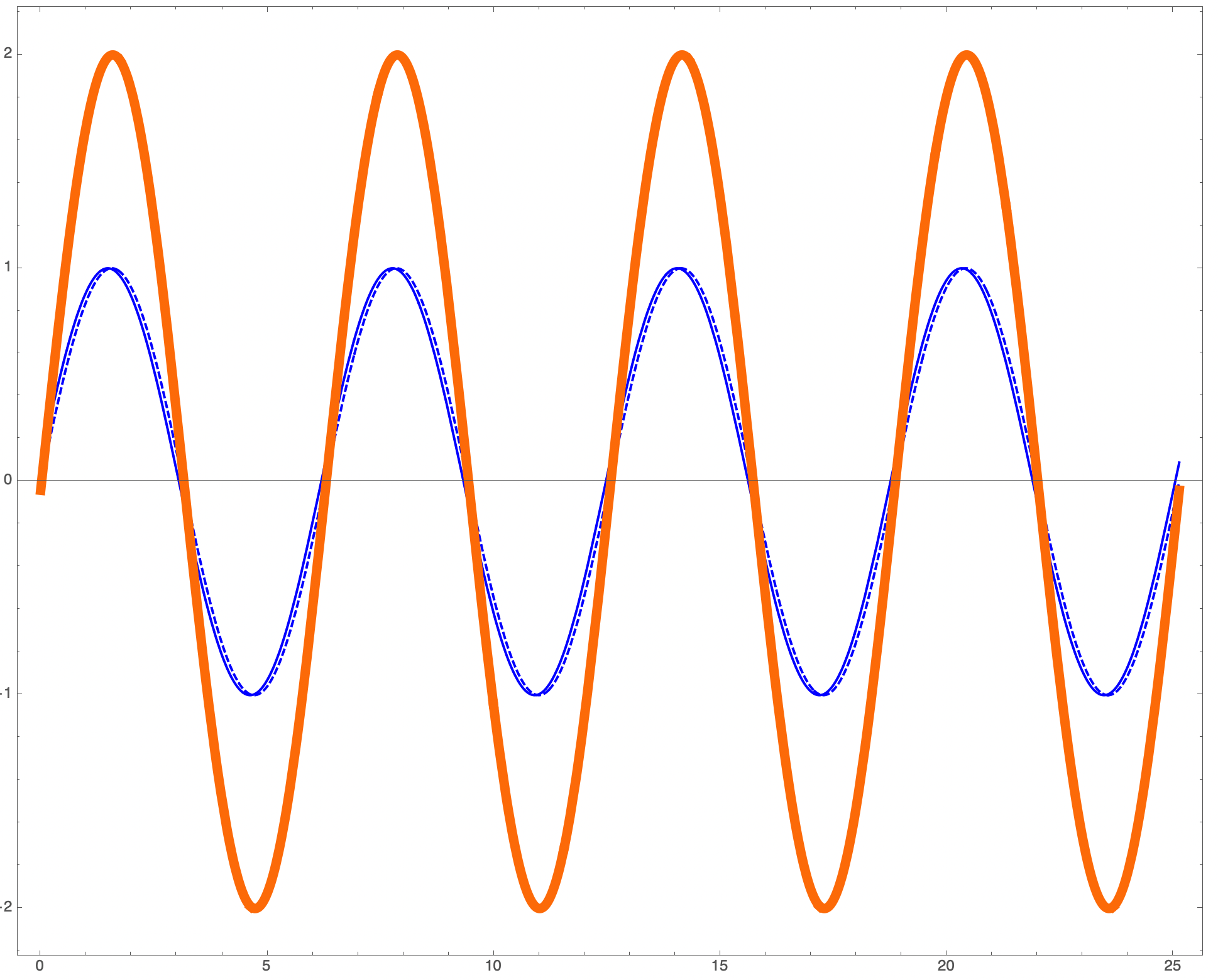

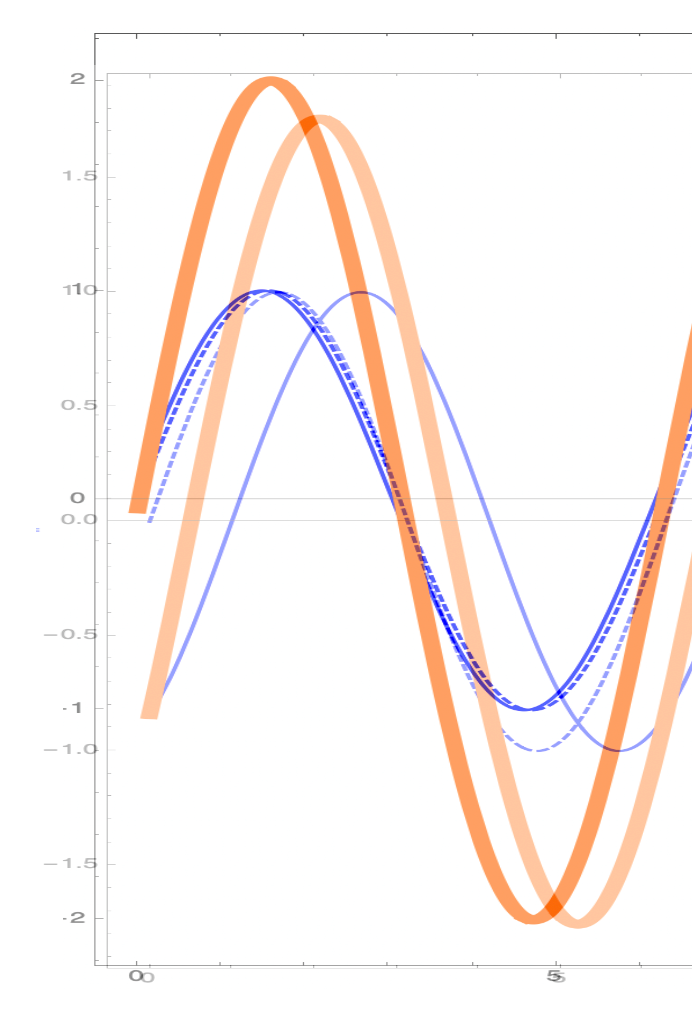

Here we have two waves that overlap and because they are completely in phase, their overlap (the orange) is at the same place as the two initial peaks.

Fig. 1.10 The dashed and solid blue lines represent waves that are brought into contact where they overlap. Notice that the two originals are absolutely in-phase and so their inference pattern is a bigger wave centered at their common peak.¶

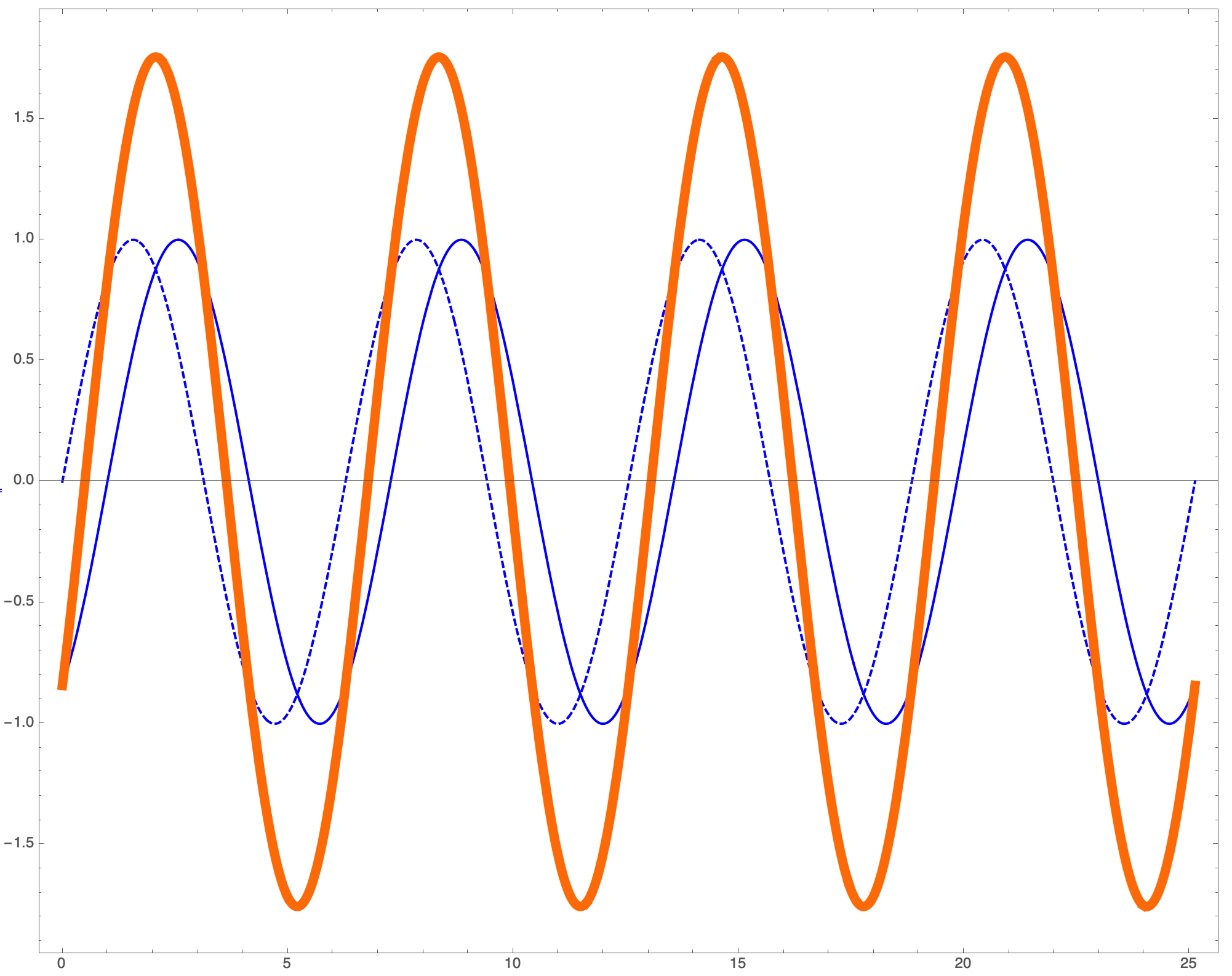

Now let’s suppose that the two initial waves are out of time with one another, as if one arrived before the other.

Fig. 1.11 Here, the two initial waves are slightly different in phase–as if they one arrived before the other. Now they peak when superimposed, but at a different point than either of the peaks.¶

Notice that the two orange curves in the two figures are slightly offset. Here’s a superposition of the two figures for the first cycle. I’ve stared the dashed initial curve for the out-of-phase scenario at the same point as the common, in-phase scenario.

Fig. 1.12 The first cycle of the previous two pictures showing the fringe shift in detail.¶

Michelson expected to see the “fringe shift” of the light-orange curve, lagging the in-phase curve as one leg of his interferometer went against the ether or along with the ether.

1.3.2. With The Phone Guy’s Help¶

With financial assistance from Alexander Graham Bell and a German optical company, in 1881 Michelson built an exquisitely precise interferometer which combined waves in exactly this way.

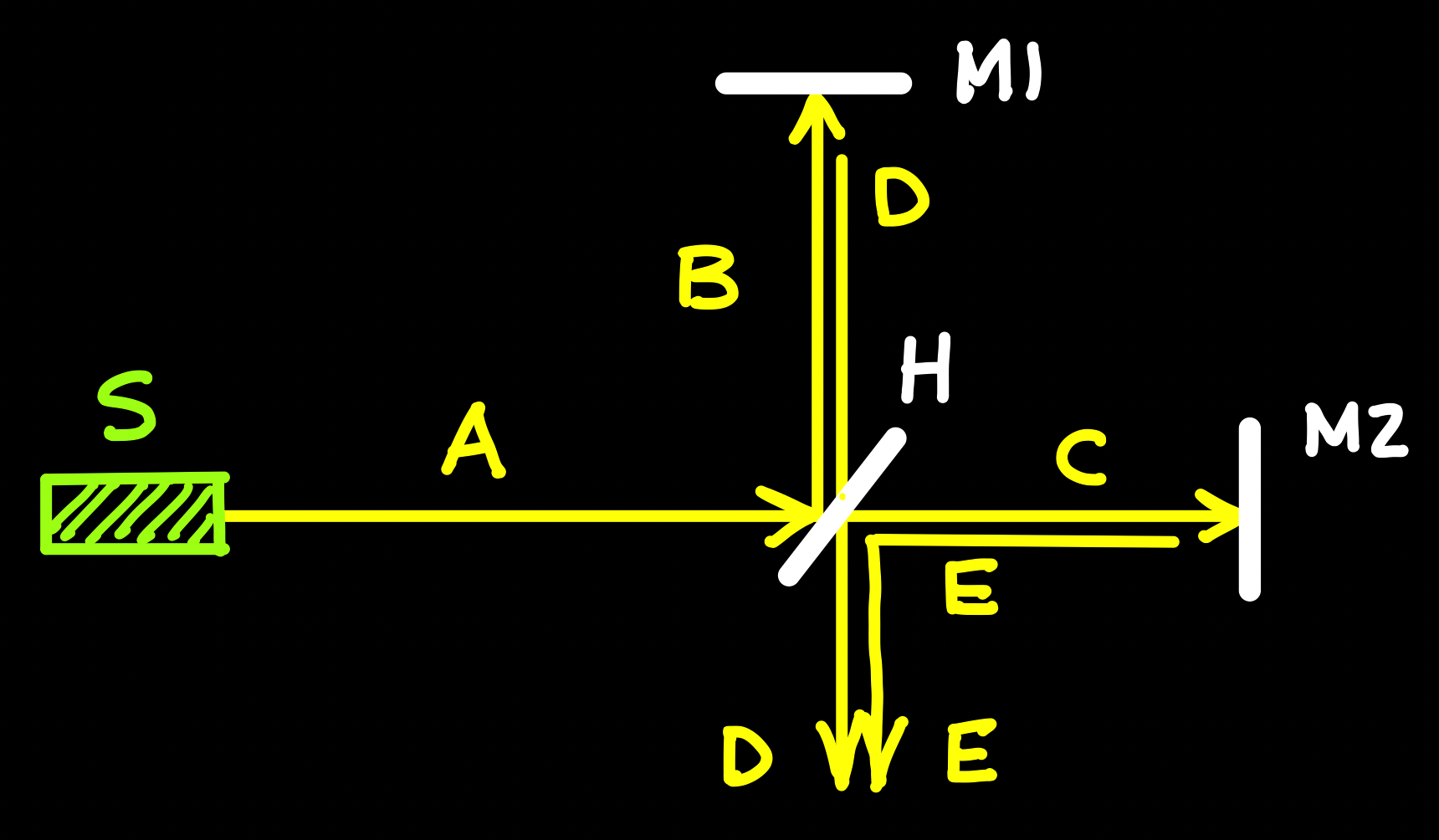

Here’s a cartoon illustrating how this worked, the device that’s riding on the moving Earth:

Fig. 1.13 Light from the source, S, is separated at H by a mirror that lets half of the light through and reflects half. The reflected piece goes up on path B, is reflected from mirror M1, and returns on path D all the way to the bottom. Meanwhile, the light that passed through H continues to the right along path C and is reflected from mirror M2 and returns to H where it’s reflected down along path E. The two beams are then combined at the bottom.¶

His first prototype had arms about a meter long.

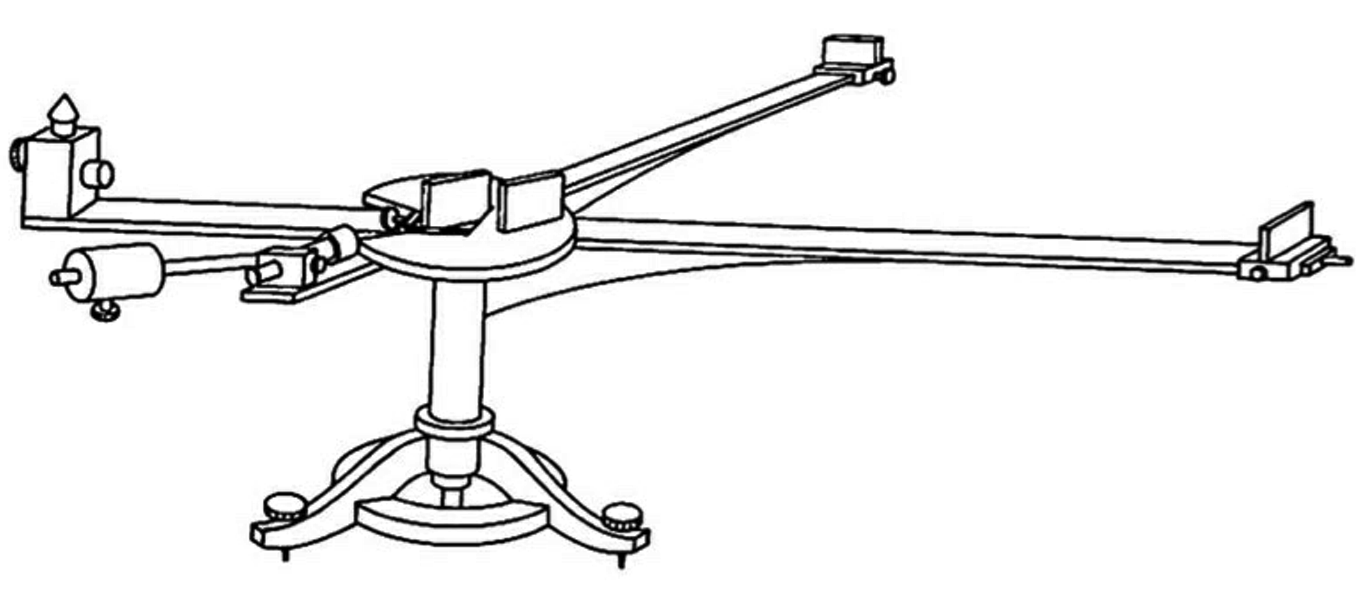

Fig. 1.14 This is a perspective engineering drawing from Michelson’s Potsdam apparatus.¶

He knew how accurate his device needed to be because the effect of the two light beams would be of the order of

This required a ridiculous level of precision, which Maxwell had calculated and decided it to be impossible. His first instrument was not up to it as even traffic outside of the lab building was sufficiently disruptive to ruin his measurements. He subsequently moved it to a basement in a lab at rural Potsdam in suburban Berlin where the measurement was better, but unsatisfying. After more than six months of painstaking work, he published his results and wrote to his benefactor:

Heidelberg, Baden, Germany

April 17th, 1881

My dear Mr. Bell,

The experiments concerning the relative motion of the earth with respect to the ether have just been brought to a successful termination. The result was however negative…

At this season of the year the supposed motion of the solar system coincides approximately with the motion of the earth around the sun, so that the effect to be oserve [observed] was at its maximum, and accordingly if the ether were at rest, the motion of the earth through it should produce a displacement of the interference fringes, of at least one tenth the distance between the fringes; a quantity easily measurable. The actual displacement was about one one hundredth, and this, assignable to the errors of experiment.

Thus the question is solved in the negative, showing that the ether in the vicinity of the earth is moving with the earth; a result in direct variance with the generally received theory of aberration…

N.B. Thanks for your pamphlet on the photophone.

The speed of the ether relative to the Earth is zero. It was the first failure that Michelson had endured in his so-far, distinguished career as the young King of Optics.

1.4. The Fallout of Michelson’s Null Result¶

There was very little reaction to Michelson’s Potsdam experiment. Hendrik Lorentz – another “king,”(whom we’ll meet in a later lesson) this time of electromagnetic, pointed out a numerical mistake in Michelson’s analysis but it didn’t change the result: still zero.

Fig. 1.15 Hendrik Lorentz

1853-1928¶

Hendrik Lorentz was the undisputed expert in the mathematics and physics of Maxwell’s electromagnetism and extended it in a crucial way. Maxwell’s equations describe the electric and magnetic fields due to extended charge distributions – “stuff” that you could hold in your hand.

Lorentz, however, was a firm believer in the atomistic picture and that the atoms included “electrons” which when they oscillated, radiated electromagnetic waves. (Notice, this was before our electron was discovered so Lorentz’s “electrons” were not what we think of as electrons today…they were just hypothetical charged components of an atom.) In 1887 he worked out the equations for the motions of his “electrons” and today we call these the Lorentz Force equations. His theory required that the motions of the electrons be related to the stationary coordinate system defined by the ether and so he was interested in Michelson’s 1881 Potsdam results since they were inconsistent with his theory. Indeed, he criticized Michelson’s conclusions in which he postulated that the ether was dragged by the Earth, and so no speed would be detected in his apparatus.

In order to study the results, Lorentz built a model and calculated what the electric field would be like for a moving charge…like in the materials of Michelson’s instrument…and what he found was that materials would actually shrink in size along the direction of the motion relative to the ether. An actual mechanical change of size. In our river analogy, my trip up and downstream would take longer than across but it could be brought to coincidence with your across-trip if my distance \(L\) was shorter by

Pencils Out! 🖋 📓

The Irish physicists George FitzGerald originally thought of this, but without a model to illustrate the shrinkage. While this is not the actual case, that square root factor will be a big part of our lives for the next few lessons!

1.5. Getting Serious: The Michelson-Morley Experiment¶

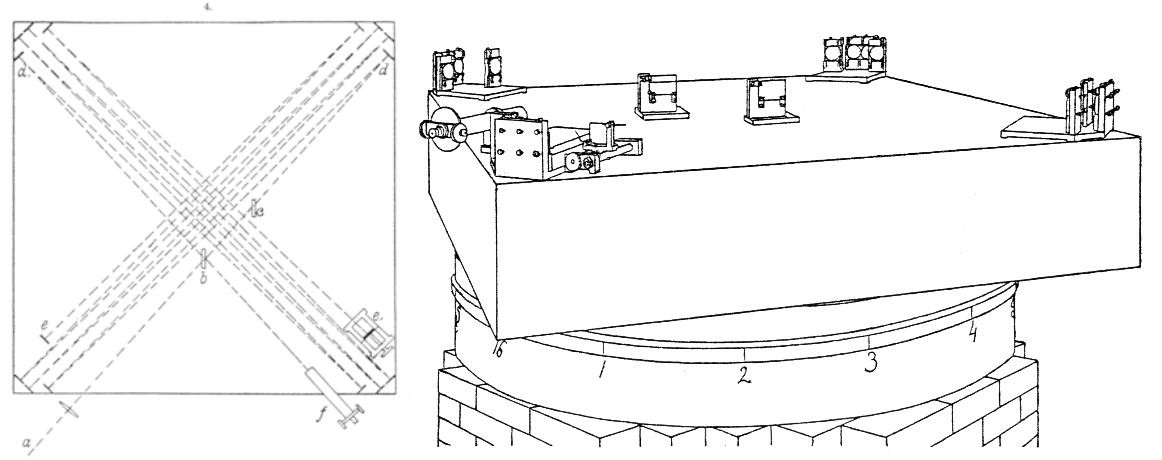

When Michelson’s time in Germany (and Paris) was done, the future was uncertain and so he was delighted to discover that colleagues had interceded on his behalf to offer him a faculty position at the brand new Case School of Applied Science in Cleveland, Ohio. (This is now the very fine Case Western Reserve University.) With sufficient startup funds and laboratory space, Michelson readily accepted the position, resigned from the Navy, and in 1881 re-established his light-speed measurement work in Cleveland. There he teamed with Case chemistry professor Edward Morley (1838-1923) to do it better. Fig. 1.16 shows an engineering drawing of the apparatus that they constructed.

Fig. 1.16 An enegineering drawing of the Michelson-Morley apparatus. Notice the many paths that the light is guided to take, thereby greatly increasing the overall length, and hence, sensitivity.¶

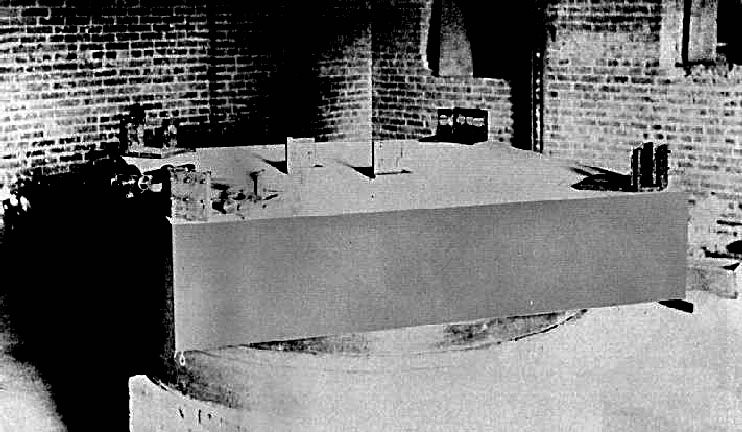

Fig. 1.17 Photograph of the Michelson-Morley apparatus.¶

Outside vibrations had been a problem in Berlin and while reduced in Potsdam, they were still a problem. What they did was build the new apparatus on a huge, heavy sandstone slab that floated in a pool of mercury–a dangerous environment. This isolated it vibrationally and allowed the experimenters to keep the whole instrument in constant rotation, slowly, so that the directions of the arms are constantly, uniformly changing. That would eliminate any potential bias. Furthermore with high quality mirrors the light paths were essentially increased back and forth to 36 meters in effective length which greatly improved the precision.

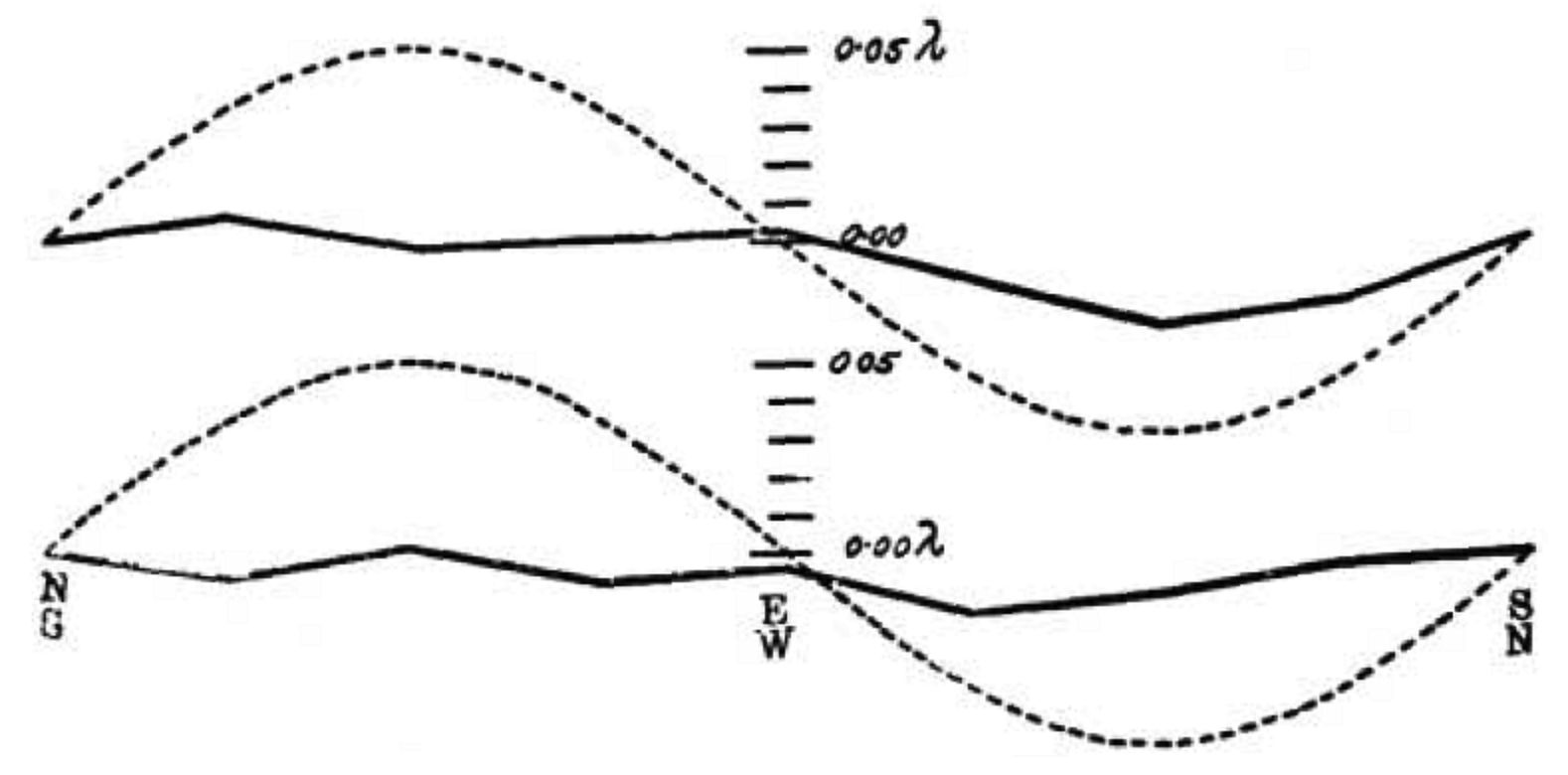

So on six days in July they did their experiment walking around the circle looking into the eyepiece all the while in 30 minute shifts each. Here are their results:

Fig. 1.18 The sine-wave curve is what they expected to see as the slab rotated around a full circle. The vertical axis is the amount of fringe shift in fractions of the wavelength of the light. The sort of sad, flat curve is what they actually measured.¶

In August, 1887, Michelson wrote to John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh – future Nobel Laureate and another king of physics:

The Experiments on relative motion of earth and ether have been completed and the result is decidedly negative. The expected deviation of the interference fringes from the zero should have been 0.40 of a fringe — the maximum displacement was 0.02 and the average much less than 0.01 — and then not in the right place.

As displacement is proportional to squares of the relative velocities it follows that if the ether does slip past [the earth] the relative velocity is less than one sixth of the earth’s velocity.

The result is unequivocally zero. For Michelson it was a failure. Either the ether moves with the Earth or there is no ether. Or something else, like Lorentz’s hypothesis. Neither Michelson nor anyone could imagine that the ether didn’t exist.

1.6. Michelson and Chicago¶

His work with Morley exhausted him and he literally had an emotional breakdown that required hospitalization. As I noted, his loving wife actually sought to have him committed (which, imagine that, created considerable tension to their relationship) and he spent months recovering in a New York institution with serious emotional and mental incapacitation. Case actually replaced him on the faculty (!) as it was presumed that he’d never recover nor do science again. Fortunately, he recovered after a couple of months and returned to try to piece together his career and his marriage. The former recovered, but the latter was troubled until it ended 13 years later. Michelson moved himself into his own quarters in their large Cleveland house and by many accounts, his personality changed after these two betrayals becoming cynical about his relationships going forward. By the way, he was reinstated on the faculty…but told by the Board of Trustees that his salary would have to be cut in order to help pay for his (unnecessary) replacement.

By 1888 Michelson was unhappy at Case. There was the on-again, off-again, strange replacement of Michelson’s position. Furthermore, there was a huge fire on campus in 1886 that destroyed Michelson’s laboratory forcing him to move into Morley’s lab and he could not get funds to rebuild his own space. The family had been through two more disasters in 1887 in Cleveland. A cook actually robbed them of their jewelry and other valuables (which were recovered in another town). And, in 1887 that maid accused Michelson of sexual assault actually leading to his arrest at home with headlines in the paper! Blackmail had been demanded and Michelson, Morley, a lawyer, and the Cleveland police actually set up a sting operation to get the perpetrator to expose her plot exonerating Michelson.

The lack of an ether would seem to pale compared to these events, but it didn’t.

When a Clark University was started in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1889 Michelson jumped at the chance to restart his program as the first Chair of Physics with finally adequate financial and technical support. In retrospect, Case had made a terrible mistake. Off they went to the New England countryside. It wasn’t a match made in heaven for any of the faculty recruited to Clark. By 1892, Michelson and almost all of the Clark faculty resigned in unison because of an unbearable meddling by the university president who was on an entirely different course from the founder and financial benefactor, Jonas Clark. It was a mess. Today, Clark University is a thriving institution. But another one bearing the distinction of losing Michelson. To the new University of Chicago in 1892.

Michelson divorced and then remarried in Chicago and he and his new wife had three more children. His first wife created a wall between her and their children that Michelson was unable, or unwilling to break through and he had no contact with them for decades.

His time at Chicago was productive and pleasant. His students enjoyed him. He played tennis regularly and had a productive and well-staffed laboratory and was able to watch his new family grow up. He was in demand around the country and the world and took on new and engaging experiments with enthusiasm and his characteristic talent for precision optics. The projects he took on included:

The measurement of the radius of a star – initially the red giant, Betelgeuse using interferometry – essentially capturing light with two telescopes and letting them interfere. In effect this increases the resolving power (or effective size) of any single telescope by a considerable factor. This is a standard technique especially in radio astronomy today.

He was commissioned to create a standard of length to augment or replace the precious, single physical meter bar in Paris. This he did by counting wavelengths of sodium vapor light so a standard meter could be reproduced anywhere in the world.

He continued his speed of light measurements and was engaged in a long-baseline experiment in California when he passed away.

He created and perfected the creation of very precise diffraction gratings with an engineered instrument in the basement of the physics building. They were the best in the world and required weeks of patient, delicate fabrication.

Oh. And he won the Nobel Prize in 1907, the first American to do so. The prize was not for the ether experiment, as Special Relativity was still only a year or so old and Einstein was still unknown. Michelson’s award reads: “for his optical precision instruments and the spectroscopic and metrological investigations carried out with their aid.”

Michelson died at the age of 79 in Pasadena, California where he was engaged in a multiple experiments to improve the precision of the determination of the speed of light. He and his wife had retired from the University of Chicago and moved the previous year so he could focus on the culmination of nearly a half century of steadily improving this measurement. He had had multiple operations for prostate and intestinal disease with multiple infections (before the time of antibiotics). This final experiment involved the construction of an evacuated tube about a mile long in the mountains of Irvine Ranch near Santa Ana, California. With multiple reflections, the path length was effectively more than 5 miles. Their biggest hurdle were the tiny geophysical shifts in the mountain range. He worked right to the end, from bed, often dictating instructions and publication drafts.

Today the determination of the speed of light is exquisitely precise using lasers: but the technique is still essentially the same one that Michelson pioneered while he was in the Navy. Likewise, his original notion of measuring the size of a star using two small, but widely spaced optical receivers and letting the interfering pattern determine the angular size of the star is now the standard technique of radio astronomy for huge radio telescopes around the world. Finally, the Michelson Interferometer is a standard bench instrument in optics labs everywhere and is the principle that was deployed in the LIGO experiment that has recently discovered Gravitational Radiation and has initiated a whole new branch of astronomy by studying the collisions of neutron stars and black holes.

1.7. More Trouble With Light¶

Einstein often asked deceptively simple questions. Here’s one from when he was 16 years old. Remember that electromagnetic waves propagate because the electric and magnetic field vectors mutually nudge one another:

A changing electric field creates a changing magnetic field and

A changing magnetic field creates a changing electric field.

And so it goes: the result is an electromagnetic wave in which the two are coupled together and self-generate their propagation.

Teenage Einstein wondered what would happen if an observer were to speed up alongside of a light beam so that she was traveling at the same speed as the light? The “changing” pattern of the two field vectors would stop if you’re right alongside. And, if they aren’t changing in time, then there’s no mutual influence of one on the other and there’s no wave.

Not only that, time would appear to stop. For example if you were watching the hands on a clock as you sped away, the reflected light from the clock hands would struggle to keep up with you if you’re traveling at near-light speeds. When you reach \(c\), all you would see would be the clock hands frozen at the last moment before the reflected light could no longer reach you.

That was a problem for which he had no solution. And it nagged him into adulthood.

1.7.1. EM Weird #1¶

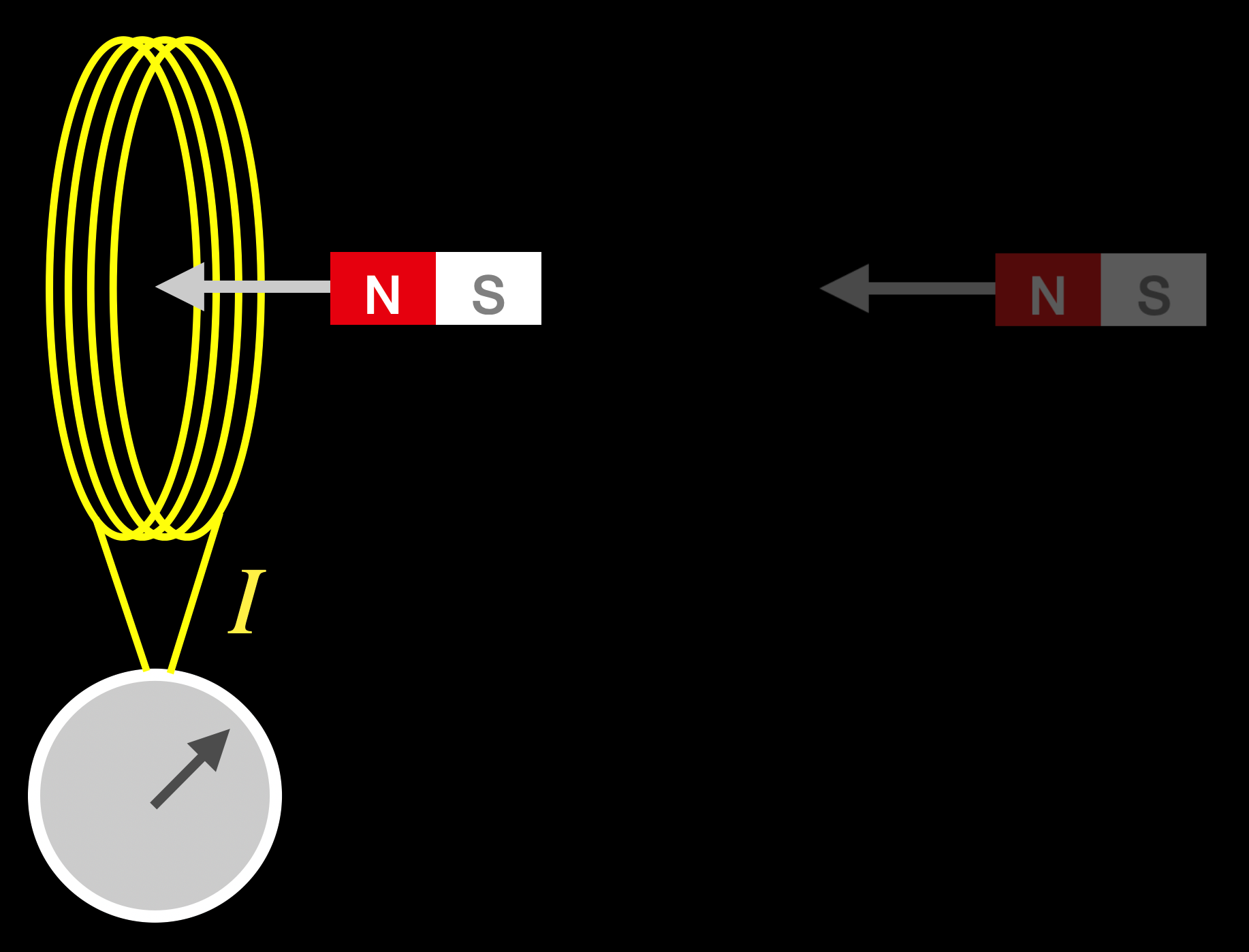

Remember my fascination with the current loop and a magnet? This is why.

Note

Watch closely: this is a strange situation.

Let’s define our two different scenarios:

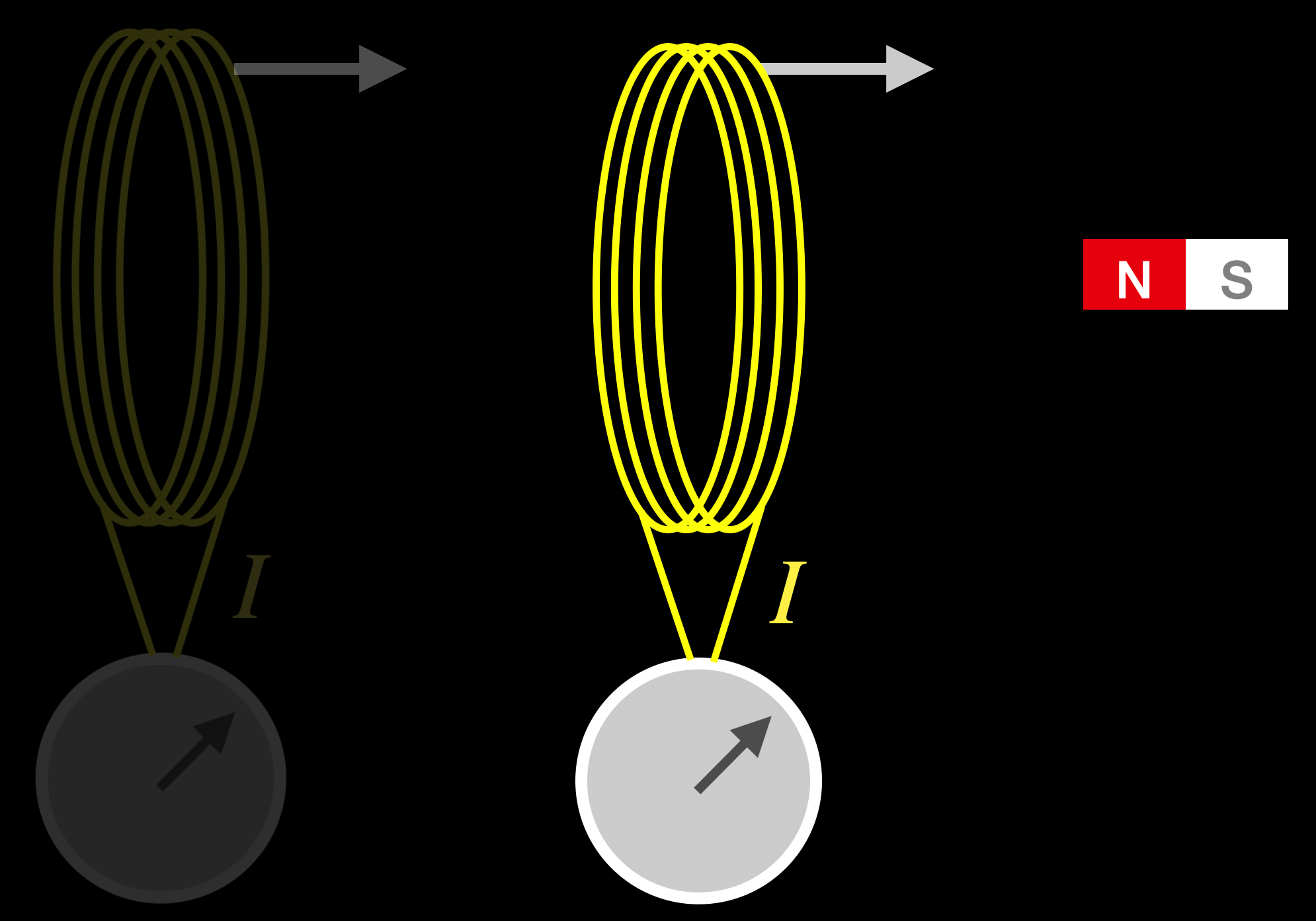

In the first part of the video, the coil is stationary with respect to the desk and the magnet is in motion. Call this scene: “Coil Stationary,” CS.

In the second part of the video, the magnet is stationary with respect to the desk and the coil moves. Call this scene: “Magnet Stationary,” MS.

Fig. 1.19 A cartoon of the “Coil Stationary” (CS) situation.¶

Fig. 1.20 A cartoon of the “Magnet Stationary” (MS) situation.¶

The result is identical: Both CS and MS cause a current and the galvanometer shows that.

Wait. What’s the problem?

Glad you asked: The problem is that the reason that a current flows in CS is due to an entirely different physical process than for MS.

We get the same result for two circumstances that only differ by the relative motion of the two pieces. But, the physics reasons are entirely different!

CS. Like Maxwell said and his equations would require, in CS the moving B field creates an E field in the vicinity of the wire in the coil. That E field in turn applies a force on the electrons in the wire and a current flows.

MS. Like Maxwell said, and his equations would require that in MS at my desk there is no E field produced because the B field does not change in time. But, the electrons in the wire are moving with the coil as it’s shoved toward the magnet and so they have a velocity relative to that B field. Lorentz’s force then causes the electrons to feel a force perpendicular to their velocity–and so they move! Inside of their wire in the coil, which is a current!

Here’s another one.

1.7.2. EM Weird #2¶

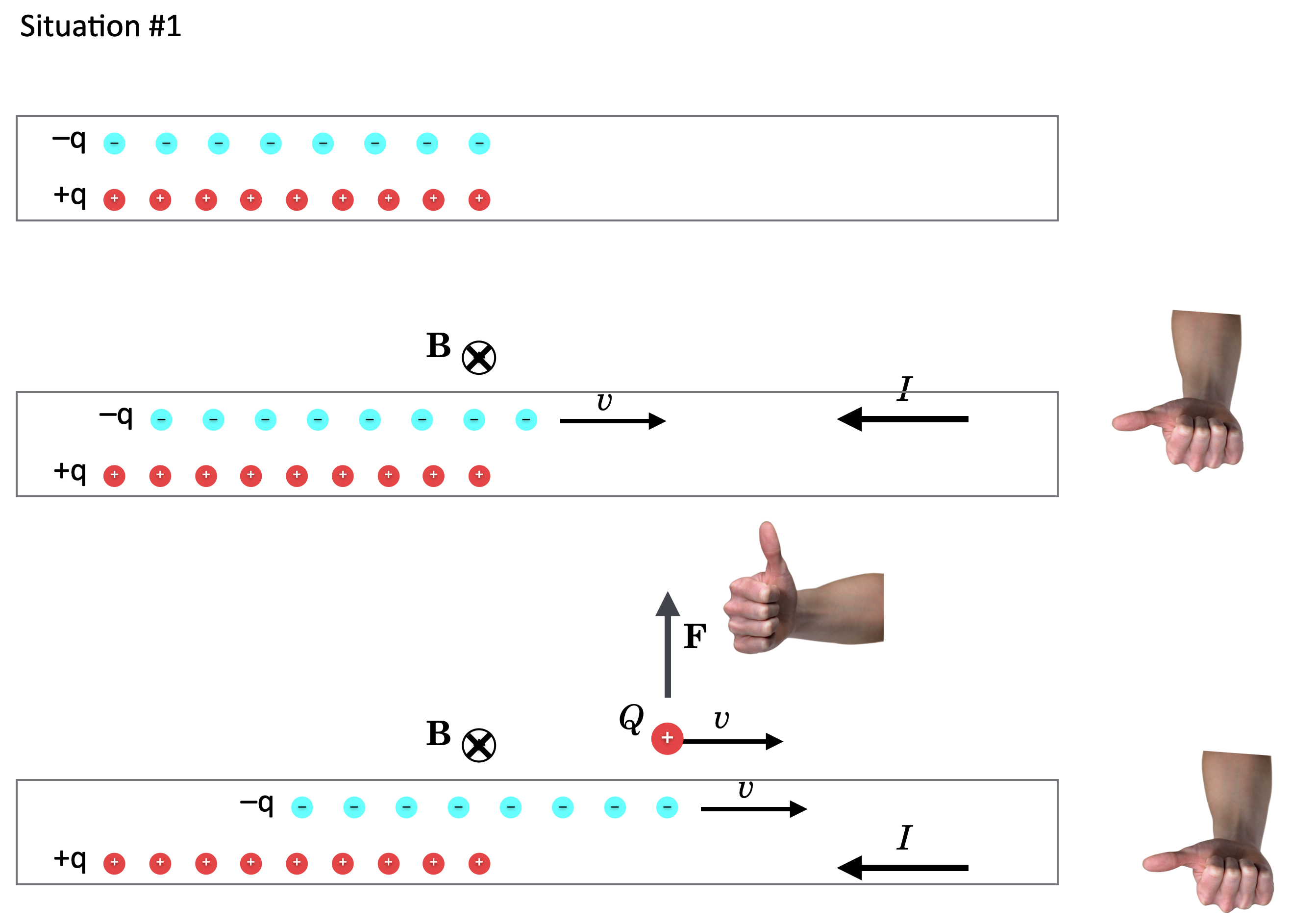

Scenario #1, which I’ll call “Q moving,” QM. Imagine that we have two lines of charge, one positive and one negative and each with the same number of \(+q\) and \(-q\) elements as shown in the top of the figure. Now we cause the negative line of charge to move to the right as in the middle figure so sitting outside of them, it would appear that there is a current \(I\) flowing towards the left (remember thanks to Ben, we mark current’s direction opposite to electron flow). That current would then create a magnetic field, B, in a circular shape around the line of \(-q\) charges. Using your right hand, you can see that it would come out of the screen at the bottom and to into the screen at the top, right? This is in the middle figure.

to do [figure]

Now let’s place a new, isolated positive charge \(+Q\) above the line of \(-q\)’s as shown in the bottom of the figure and cause it to have the same velocity to the right and ride along with the line of \(-q\) charges. So \(+Q\) and the negative \(-q\)’s are relatively stationary. It sees no current due to the negative line of charge, since it appears to not be moving relative to it. But it does see that same current, \(I\) now due to the relatively moving positive line of charge that appears to \(Q\) to be flowing to the left. \(Q\) now feels that B field — in at the top and out at the bottom — and so by Lorentz’s force relationship, it feels a force pointing up and so it would curve up.

Fig. 1.21 \(+Q\) moving.¶

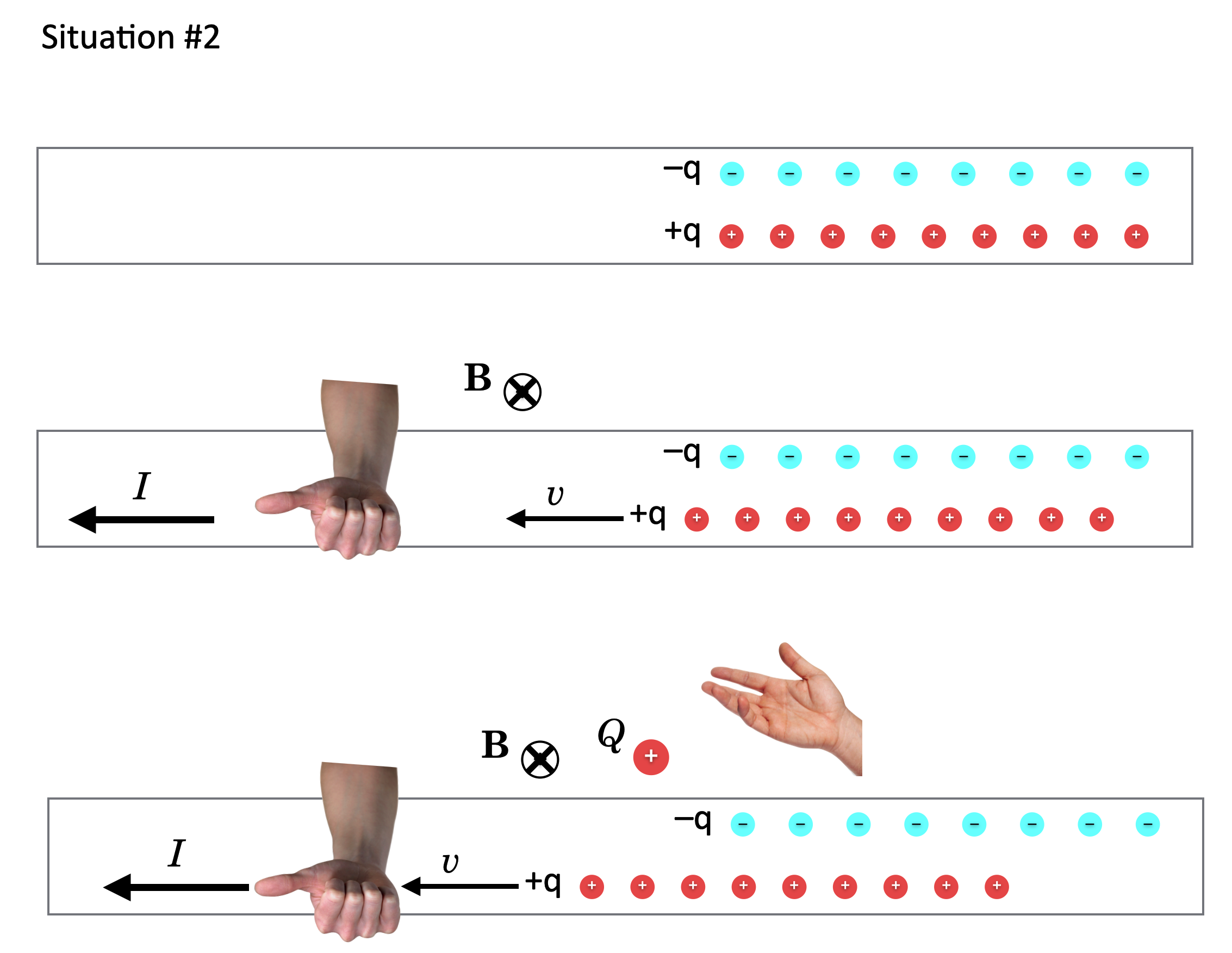

Scenario #2, which I’ll call “Q stationary,” QS. Now let’s mix it up by creating the same current in a different way. Let’s keep the \(+Q\) charge and the line of \(-q\) charges stationary (like in the top of this figure) and cause the \(+q\) line of charges to move to the left as in the middle of the figure. That also creates an identical current to the left, \(I\). So that current part of QS is the same as in QM. That moving positive line of charge’s current also creates a magnetic field with the same configuration as in QM. But! \(+Q\) is just sitting there — it has no velocity in this scenario — so it does not feel a force from B and doesn’t see a force and stays unmoved!

Fig. 1.22 \(+Q\) not moving.¶

QM and QS appear to be identical situations overall: both have a current flowing to the left and identical magnetic fields. Both have a positive charge \(+Q\) which is in the same relationship to the \(-q\) line of charge: at rest with respect to it. In QM, they both move while in QS, neither moves.

But: the physical outcome is different! In QM, \(+Q\) feels a force and would move up and in QS, the \(+Q\) would not feel a force and just stay still.

In both of these examples Maxwell’s Equations seem to fail for scenarios that differ only in the relative speeds of the observer.

So something must be wrong with Maxwell’s equations? How about Newton’s laws of motion?

1.7.3. Newton Seems Fine¶

Pencils Out! 🖋 📓

Suppose you’re in an airplane traveling at 500 km/h to the east and you’re bored so you start to roll apples along the aisle. It’s a long flight and you’ve got plenty of time to practice and you learn that you can start rolling your apple at 5 km/h and that after 2 seconds it will have slowed to 1 km/h. If your apple is like our QS&BB apples it has a mass of 0.1 kg, we can calculate the force that’s applied to the apple by the floor to slow it down:

(Of course the negative sign tells us that the force is pointing away from the direction of the velocities and so it’s decelerating.)

I’m on the ground and I’m also bored and I have a very fine telescope that allows me to watch airplanes as they fly overhead. It’s a comic-book telescope and so I can see through the hull and into the airplane and I can watch you roll your apple. What would I say is the force that the carpet is exerting on your apple to slow it down?

Just as you’d expect: Newton’s laws of motion work just fine between two systems that differ only by their relative speeds. Remember this moment.

Note

Two great theories – of electricity and magnetism and mechanics – behave very differently when applied to circumstances that differ only by the state of motion of the observer. Circa 1900, here’s the what people were convinced of:

Count on it: 1. Newton’s laws of motion are well behaved.

Count on it: 2. Maxwell’s equations of electromagnetism fail outside of the ether.

That’s a disaster and it bothered Albert Einstein during a particularly important year in his life which we’ll talk about a lot in the next lesson.

But let’s go to the airport and think about moving sidewalks.

1.8. Frames Of Reference¶

I’ve not been able to make fun of Aristotle for a number of lessons and I miss that. So let’s let Galileo speak for himself and put another nail in the coffin that was once Aristotle’s physics.

1.8.1. Galilean Relativity¶

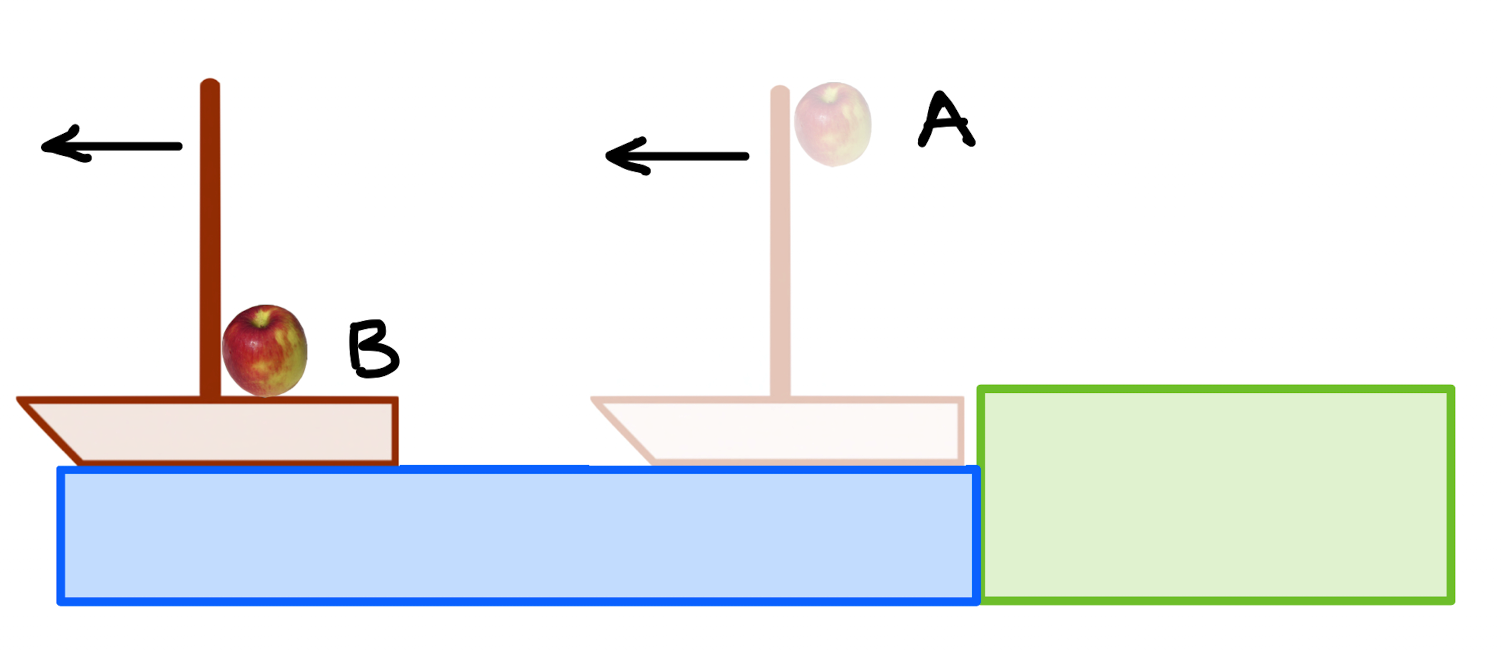

Suppose we are on a ship with a tall mast and a sailor in the crow’s nest with, of course, an apple. Let’s consider two scenarios:

Scenario #1, which I’ll call “In port,” IP. In this situation, our sailor in the crow’s nest drops his apple.

Scenario #2, which I’ll call “Under sail,” US. In this situation the ship is moving west and our sailor again drops his apple.

Mr Aristotle would have said that in IP, the apple would fall to the base of the mast, directly from \(A\) to \(B\). Galileo would agree.

Pencils Out! 🖋 📓

Fig. 1.23 In port (IP): a sailor drops an apple from the crow’s nest and if falls directly to the base of the mast. Both the sailors on board and observers on the shore agree.¶

But Aristotle would say that in US, the apple would fall to the east of the ship, to \(C\) since the ship has sailed right out from under it. Here you see the ship moving to the left (west) and the apple making a strange journey from \(A\) to \(C\):

Fig. 1.24 Under sail (US): now the ship is moving relative to the shore. The sailor drops her second apple and Aristotle would say that it falls direclty down relative to the shore and that the ship moves out from under it.¶

Does this make any sense to you? (Think about your apple-roll on the airplane.) Of course not and like so many other times, Locomotion for Aristotle fits his complicated philosophical system, but fails to match even the simplest glimpse of reality.

“Observation versus Authority: To modern educated people, it seems obvious that matters of fact are to be ascertained by observation, not by consulting ancient authorities…Aristotle maintained that women have fewer teeth than men; although he was twice married, it never occurred to him to verify this statement by examining his wives’ mouths.” Bertrand Russell, The Impact of Science on Society, p. 7. Simon & Schuster Inc, 1968

Now, while Aristotle might have been a pretty good observer, except perhaps in matters of dentistry, he surely never dropped something from within a moving airplane, or for that matter a ship. If you’ve ever flown on a plane or ridden in a car or a train, you’ve probably dropped something. It doesn’t land behind you.

But can you see that this example kind of rhymes with the examples from electromagnetism that we just went through? Something odd happens between two systems, one at rest and the other in motion.

Here’s another example, more reasonable. And a bit newer, only 400 years ago. From Galileo’s Dialogue:

“Shut yourself up with some friend in the main cabin below decks on some large ship, and have with you there some flies, butterflies, and other small flying animals. Have a large bowl of water with some fish in it; hang up a bottle that empties drop by drop into a wide vessel beneath it. With the ship standing still, observe carefully how the little animals fly with equal speed to all sides of the cabin. The fish swim indifferently in all directions; the drops fall into the vessel beneath; and, in throwing something to your friend, you need throw it no more strongly in one direction than another, the distances being equal; jumping with your feet together, you pass equal spaces in every direction…have the ship proceed with any speed you like, so long as the motion is uniform and not fluctuating this way and that. You will discover not the least change in all the effects named, nor could you tell from any of them whether the ship was moving or standing still.”

This is among the most important observations in physics. What he’s saying is that US should result in this apple’s trajectory:

Pencils Out! 🖋 📓

Fig. 1.25 Under sail (US): from Galileo’s point of view. Galileo said that the apple shares the forward motion of the ship and that it falls to the base of the mast. So to an observer on the shore, it would take a parabolic path relative to the shore.¶

We call this idea Galilean Relativity and it says that:

Galilean Relativity

There is no mechanical experiment that one can perform that can measure whether one is moving at a constant velocity or standing still.

These two circumstances, moving at a constant speed and standing still, seem like very differently things. Stay tuned.

1.9. Frames of Reference, For Real¶

Let’s think hard about something simple. What is required in order to determine motion? To measure the speed of a car for example, we could lay out a series of rulers along the side of the road and then drive the car at a constant speed while starting a clock inside the car at the beginning and stopping it at the end. If we drove past 100 meter sticks and it took 10 seconds, then we might conclude that our speed was \(v= \frac{100}{10} = 10\) m/s.

Note

Our first deep thought about ordinary things: Notice that the meter sticks were on the ground but our clock was in the car. You wouldn’t ordinarily find that a problem, right? But this is just the first of the ways that we’ll need to be very careful about what we mean when we discuss simple things.

How might we make a measurement of speed with both a clock and a meter stick in the same place? The way your car does it is by measuring how many times your (known-sized) tires turn during a given time. One trip around for a 26.1x8.9R19 tire has a diameter of 26.1 in, so a circumference of \(C=D\pi= 82\) in. So once around translates to a trip forward of 82 inches. So counting the rotations with an inside clock would be a measurement of the speed of the car using only tools within the car. (And that’s how your speedometer calculates speed. Change your tires’ sizes and you’ll mess up your speedometer and odometer.)

How about measuring speed but only using tools that are on the road? Laying out the meter sticks beforehand is simple. But what do you do about the time measurement? You’d want for a clock on the road to start at when you pass the first edge of the first meter stick and a clock to stop when you passed the last end of the last meter stick. But how do you ensure that the two clocks are calibrated with respect to one another? How might you do that?

Here’s an elaborate scheme, which is actually overblown, but something like this has to occur. Let’s set up two toy trains next to the string of meter sticks, each located at the center of the string and each pointing to one of the clocks at the ends. The toy trains’ jobs are to travel in opposite directions and start the clocks when they arrive. Then we know that they would have both been started at the same time.

Now we let them run and they have digital displays that show the seconds as they go. If the east clock says 20 seconds, then the west clock will also report 20 seconds. They’re now calibrated. Let the clocks continue to run, just counting seconds. We can be sure that they are synchronized.

Now we drive by. When we pass the east clock, we write down the time that first clock is reporting…we travel that 100 meters and then write down the time that the west clock displays. If we subtract the times, we know how much time elapsed in our 100 meter trip – using tools – meter sticks and clocks – which are all located on the road.

Notice that “on the road” is a way of saying that the clocks and the meter sticks all are stationary with respect to one another. Likewise, our tire-clock mechanism is the same way, stationary with respect to the car itself. No mixing of tools and no relative motion among the tools.

In order to make this measurement, we had to calibrate – synchronize – those two clocks.

Wait.

So, what’s the big deal? In fact, aren’t you making a simple thing too hard?

Glad you asked:

Seems like it, doesn’t it. But this clock synchronization issue becomes a critical part of Einstein’s relativity and messes with space and time forever more. Stay tuned.

The point is – apart from setting up a surprise later – is that we can completely specify motion with a meter stick and a clock. In fact, that’s going to be our definition of a Frame of Reference:

A Frame of Reference

is a system in which a length and a time can be determined from within.

So, we think of every frame of reference as having a ruler and a clock. In fact, all objects which share a Frame of Reference are at rest with respect to one another.

An Inertial Frame of Reference

is a Frame of Reference which is not accelerated…moving at a constant velociy (which could be zero).

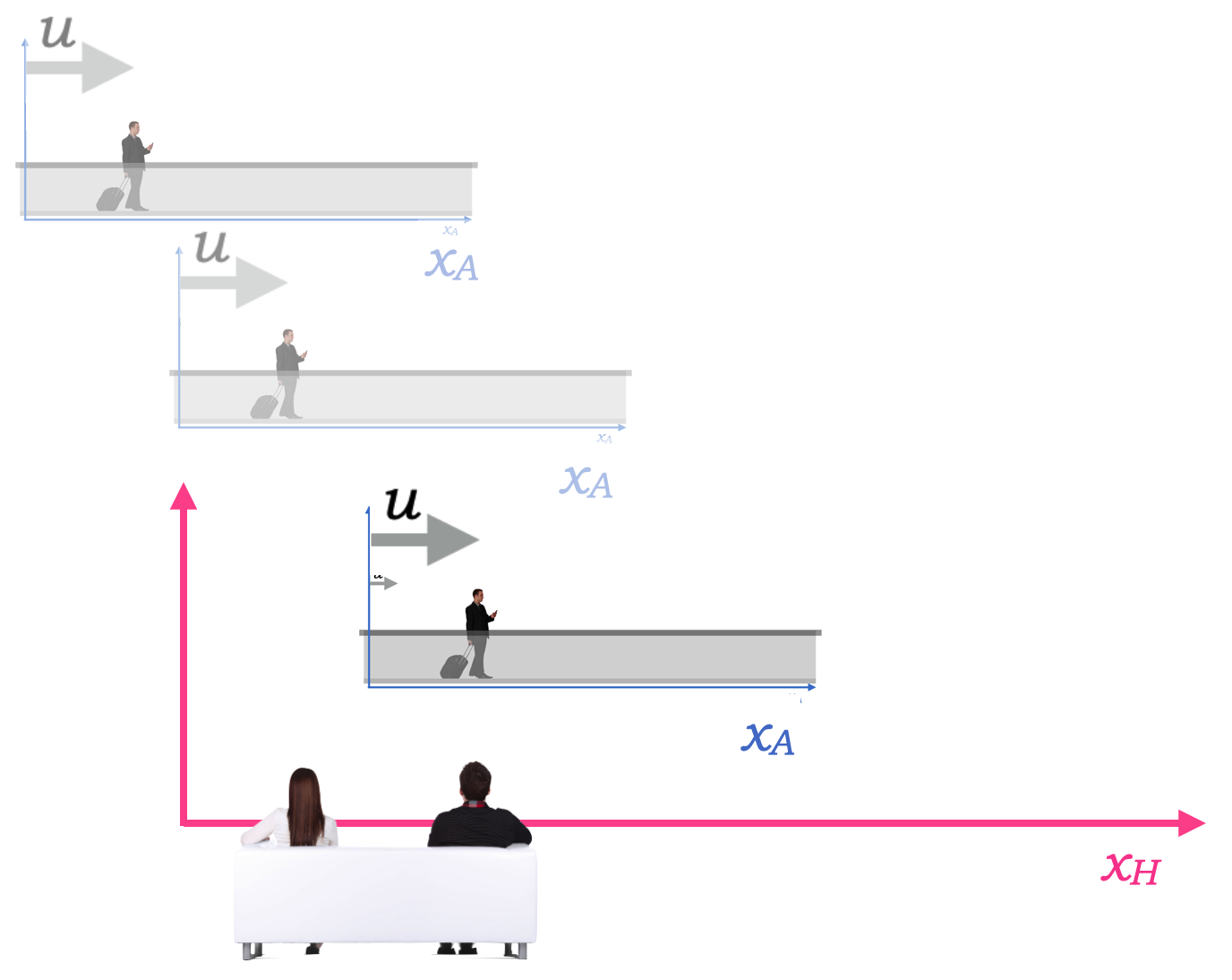

We will need to make reference to Frames of Reference many times and I’ll use a variety of pictures to show two frames that are moving relative to one another. They are all meant to portray the same circumstance, like cool guy and old guy here:

Please answer question 1 📺

Each guy has a coordinate system attached to them that allows for measurement in the three space directions and each of them has a watch. Cool guy appears to be in motion towards us while old guy appears to be stationary. That’s because we’re viewing them from old guy’s “reference frame.”

But what does cool guy see? In his reference frame he’s stationary and old guy is moving backwards towards him. Each of them has his own unique frame that the other doesn’t share, their Rest Frame (also called the Proper Frame):

A Rest, or Proper, Frame

is a special frame of reference in which clocks and rulers are stationary with respect to one another.

So our meter sticks and two clocks beside the road are in their own rest frame while we in the car with our clock and our tire-rotating-measuring-device are in our own rest frame.

It’s difficult to keep track and name the frames. We’ll often want to compare what goes on in one frame with another. Most books on Relativity will represent the space and time coordinates in a frame moving relative to a rest frame with primes, like \(x'\) or \(t'\). We’ll do it differently and always consistently:

Home and Away

A rest frame we’ll call “Home,” \(H\).

Any frame moving relative to Home will be called “Away,” \(A\).

This nomenclature makes it clear who is who and so instead of \(x'\) I’ll write “\(x_A\). You’ll see.

So here’s a rather typical arrangement that we’ll see a lot.

Pencils Out! 🖋 📓

Fig. 1.26 We’ll see this over and over: a Home Frame and what appears to be a relatively moving Away Frame. Each is equipped with rulers and clocks.¶

Above we have home – in which the picture is drawn – and away frames which we’re viewing from the Home frame (which we always would do) from which we observe an Away Frame moving past us at a speed, \(u\). I’ll always use \(u\) to represent the speed of an Away Frame (reserving \(v\) for the speed of something moving inside of the Away Frame).

One of the standard questions is to ask how things move in the Away Frame when they’re viewed from the Home Frame. You already know how to do this.

Please study example 1 🖋 📓

Let’s go to the airport.

1.9.1. Galileo And The Airport¶

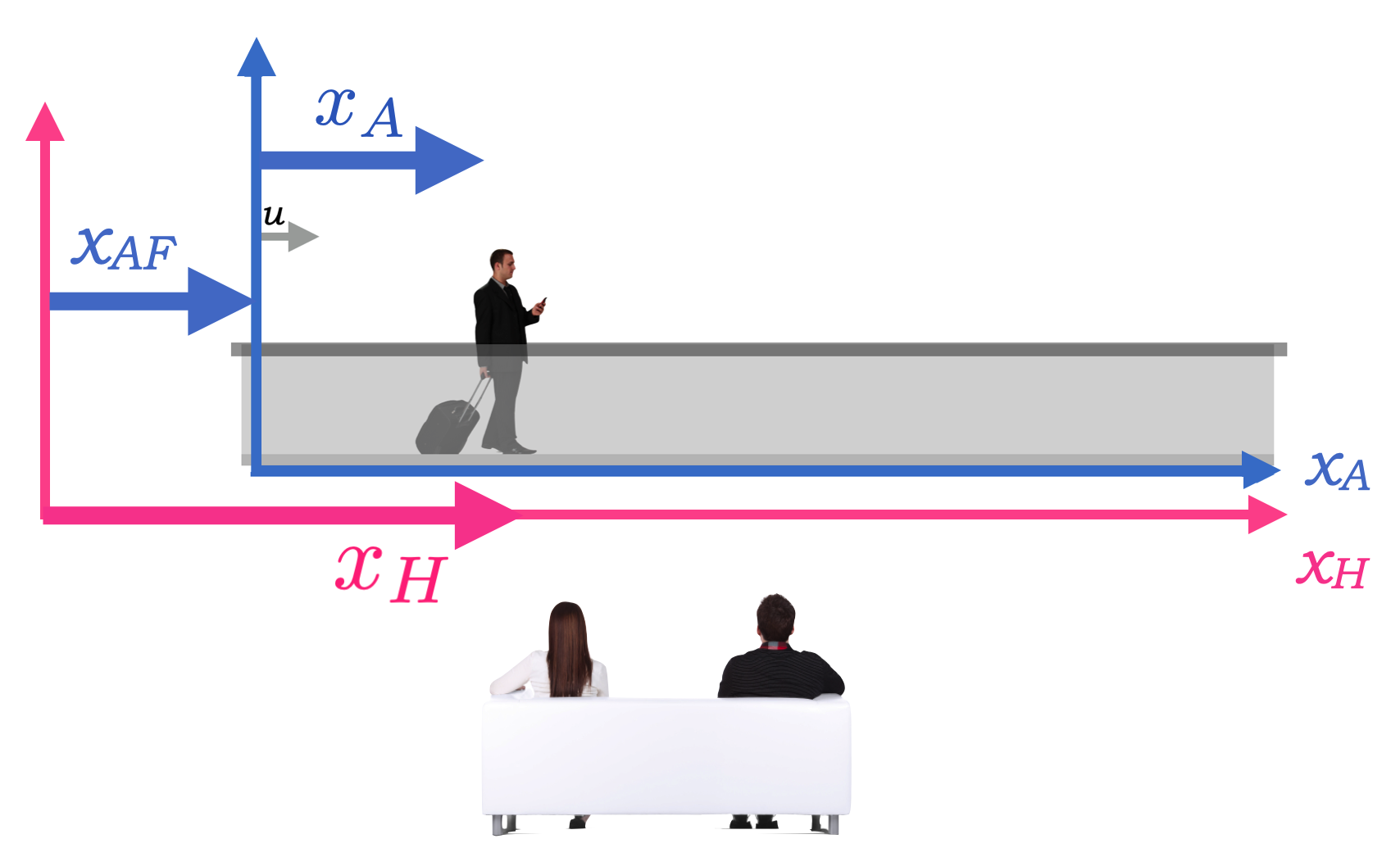

Pencils Out! 🖋 📓

You’ve all done it. You’ve sat in the airport terminal and watched the people on the moving sidewalk. There are the people who do it right and walk on the sidewalk, and then there’s this guy. The guy who just stands on the sidewalk:

Fig. 1.27 Sitting in the airport with nothing to do but watch people on the moving sidewalk. Here we see Sidewalk Guy moving with the sidewalk at velocity \(\vec{u}\). To Couch People – they’re in the (their) Home frame and he and the sidewalk make up the Away frame.¶

Notice that we’ve got our two frames: Couch People sitting in the terminal are occupying the Home frame while Sidewalk Guy is standing on the sidewalk looking at his phone. When the two vertical axes align, like the middle of the three scenes above, both Couch People and Sidewalk Guy start their clocks so that both have a \(t=0\) reference that’s common.

If Sidewalk Guy is 2 meters from the origin of his coordinate system (\(x_A=2\)) and if the sidewalk is moving at \(u=2\) m/s, then after 2 seconds what is the distance that Couch People would say that Sidewalk Guy is at in their coordinate system? That is, what is \(x_H\)?

Here’s the situation.

Fig. 1.28 Now more quantitatively: \(\vec{u} is the velocity of \)A\( relative to \)H\(; \)x_A\( is the position of Sidewalk Guy *relative to his coordinate system* which is attached to the sidewalk with the origin as shown; \)x_{AF}\( is the position of Sidewalk Guy *relative to the airport, Couch People's \)H$ frame.¶

Let’s be clear about what is what here. (You should draw this for yourself.)

\(x_{AF}\) is the distance that the origin of the Away frame has moved at any time.

\(x_A\) is the distance that Sidewalk Guy is from the origin of the Away frame. That’s constant since he’s lazy.

\(x_H\) is the distance that the Sidewalk Guy has moved as measured by the couch people in the Home frame. That changes with time.

In the Away frame, \(x_A = 2\) meters, and it’s always 2 meters since he’s not moving in his frame.

In 2 seconds, how far has the sidewalk – the whole Away frame – moved? That is, what’s \(x_{AF}\) after 2 seconds? It’s simple:

A Coordinate Transformation

is transforming, or calculating, the coordinates of an event that occurs in one Frame of Reference into another Frame of Reference.

What we just did is calculate a Galilean Transformation, represented by the simple model:

So what is \(x_H\)? It’s

Note

What Galilean Relativity says is that no mechanical experiment can tell you that you’re moving or not moving at a constant velocity.

What that means in detail is that the equations that describe a mechanical process in one frame will be the same equations that describe that process in another inertial frame. So the equations that would describe a ball rolling down a ramp, or a pendulum, or tossing a baseball as described by someone in the Away frame would be the same equations as those watching from the Home frame.

Even more specifically: if you were to take the equations in the Away frame and substitute the variables from the above equation, reversed:

You’d get an equation now in terms of \(x_H\) and the \(u\) would drop out…except for the subscript \(H\) the two equations would be identical.

Please study example 2 🖋 📓

Please answer question 2 📺

Please answer question 3 📺

1.9.2. Coordinate Transformations¶

This sort of going from one frame of reference to another is a regular feature of relativity and other areas of physics. In general, what it always means is:

We will start with known coordinates in the Away frame and then a “transformation” among those \(x_A\) and \(t_A\) converts them into those variables measured in the Home frame. Or, the other way around. That transformation is just a formula, and in this case it’s the simple:

Notice that this is just like the constant speed definition from Lesson XX and the reason that’s the case is that the time, \(t\) is just a common parameter. We could plot our airport adventure easily, which is another way of solving that simple equation.

Note

Boy, is that going to change.

1.9.3. Coordinate Transformations Inside of Other Models of Motion¶

We can imagine other kinds of transformations. Look at Newton’s second law:

The quantity in the brackets is of course the speed, and the operation in front of the brackets is asking for the change of that quantity with respect to time, which is of course the acceleration.

If we were to replace the A frame variables with those transformed by the Galilean transformation, we would get:

It looks the same, except the subscript is different. That “form independence” is the hallmark of a model that doesn’t care about some transformation done on it.

Have a look at a deeper explanation 2 🖋 📓

Here it is: If one were to substitute as above:

Since \(u\) doesn’t change in time, any change of \(u\) with respect to \(t\) drops out and the final result for \(F_H\) has exactly the same form as \(F_A\). This “form independence” is important and signals that an “invariance” has been discovered. We could call the variables Sally and Bill instead of \(x_A\) and \(x_H\)…it doesn’t matter. What matters is the algebraic form of the equations.

So, mechanical equations of motion do not care about relative inertial motion. Said a fancier way: Mechanics is invariant with respect to a Galilean Transformation.

So:

Maxwell seems to fail,

Newton seems to be okay,

when comparing electromagnetic and mechanical phenomena between inertially moving frames of reference. Hold onto your hat.

You’ll never be the same in airports again.

1.10. What to Remember from Lesson 15¶

1.10.1. The Ether¶

That light needed a medium “to wave” in was the undisputed confirmed belief of all scientists for nearly 80 years since Faraday first began his systematic study of electromagnetism. The idea had problems, notably that light has such a high velocity that the stiffness of the ether material had to be millions of times more than that of steel…and yet, it had to be everywhere in the universe–in outer space and in the room you’re in now–without impeding the motions of material bodies going through it.

1.10.2. Detection of the Ether¶

Either the ether was dragged along with the Earth as it moves, or is completely stationary were two logical possibilities. Stellar aberration observations suggested that the Earth moved through the ether and it was satisfying to imagine that Newton’s Absolute Space notion had a realization in the ether itself.

So it might be possible to detect the Earth’s motion through that stationary ether by interfering two beams of light in perpendicular directions in the Michelson Interferometer, while, of course, riding on the Earth as it orbits the Sun.

Michelson’s original and then his more precise iteration with Morley at Case detected zero relative speed for the Earth and the ether.

1.10.3. How to Explain the Null Result?¶

There was no satisfactory explanation for the null result of the Michelson-Morley experiment. The least unsatisfactory way out was the idea of Lorentz that made use of his notion that atoms exist and that they consist of electrically charged particles who’s electric field would contract due to its motion with the Earth in the direction of its motion. (This particle became became the electron, after its discovery in 1897. Stay tuned.) So, it was concluded by him and by Fitzgerald (who had no model, just the idea) that the physical dimensions of the Michelson Interferometer would shrink due to its motion and the electric fields of its atoms’ interaction with the ether. While not the actual situation, some of the mathematical descriptions that Lorentz worked out have their role in Relativity which is why they are called the Lorentz Transformations, even though they more naturally “fell out” of Einstein’s model.

1.10.4. Galilean Relativity¶

This is a simple idea: there is no mechanical experiment that you can perform in an inertial rest frame that would detect whether you are moving or stationary. Working out the mechanics of such an experiment would naturally follow Newton’s laws of motion and any observer who is moving at a constant speed relative to you should be able to use the same Newton’s laws of motion to describe the motion in your rest frame as well. This suggests that Newton’s laws are “invariant” with respect to a Galilean Transformation, which is:

where the \(x_H\) represents an \(x\) coordinate as determined in that “stationary,” Home frame of reference; \(u\) represents the speed of that frame of reference relative to some other frame, called “Away;” and so \(x_A\) represents an \(x\) coordinate of the same event in that moving frame of reference.

1.10.5. Maxwell’s Equations¶

While Newton’s laws of motion are invariant with respect to a Galilean Transformation for relatively moving frames of reference, Maxwell’s Equations are not! This manifests itself in many paradoxes which Einstein focused on as troubling.

1.10.6. An Untenable Situation!¶

By the turn of the 20th century, there were two great systems in physics, both with highly confirmed mathematical structures: Mechanics was well described by Newton’s laws of motion and Electromagnetism was well described by Maxwell’s Equations, supplemented by Lorentz’s force law.

As firmly established as they were, they had completely different behaviors when they were applied to relatively moving inertial frames of reference.

How can that be?